Description of previous item

Description of next item

Quincy Goes Better with a Coke

Published January 1, 2017 by Florida Memory

Today, Americans remain sharply divided on their soda pop preferences, but in the tiny town of Quincy, Florida, the refreshing bite of Coca-Cola reigns supreme. The so-called “Coca-Cola millionaires,” and their many descendants still living in the community of just around 8,000 people, would not have it any other way. In the early 20th century, banker, Mark “Pat” Munroe, secured his fate as a local legend when he bought several shares of Coca-Cola stock soon after the soft drink company went public in 1919. He encouraged others to invest in Coke as well. What might have seemed like a gamble then ultimately paid dividends for Quincy’s original 25 Coca-Cola millionaires. In fact, just before World War II, the town of Quincy boasted the highest per-capita income of any municipality in the country, owed in large part to America’s love affair with Coca-Cola.

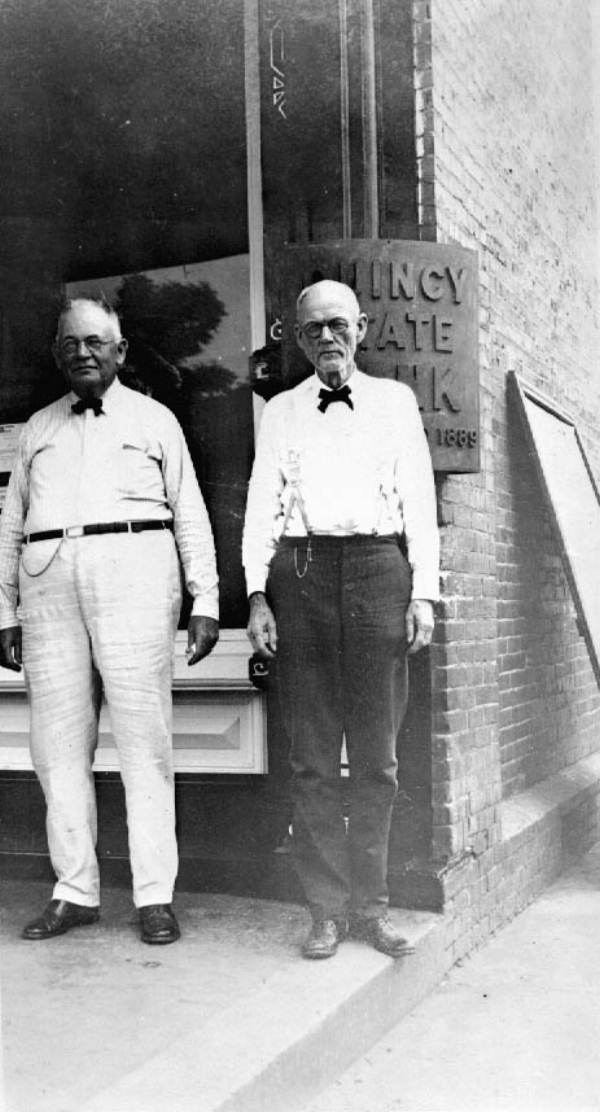

The original Coca-Cola millionaire, Pat Munroe (right) standing next to local shade tobacco producer, businessman, and fellow cola investor, E.B. Shelfer, Sr. (left) outside of the Quincy State Bank, ca. 1920.

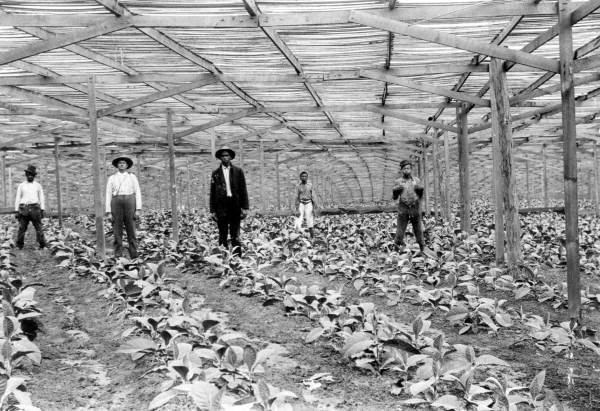

Named after John Quincy Adams, white settlers established Quincy as the county seat of Gadsden County, Florida in 1828. Located about twenty miles west of Tallahassee, atop some of Florida’s most fertile soil, Quincy’s economic history is rooted in agricultural production. Shade tobacco, used to wrap cigars, grew exceptionally well in the region’s humid climate and would eventually become the county’s most profitable industry. Prior to the Civil War, plantation owners in the area relied on enslaved labor to cultivate large quantities of not only tobacco, but also cotton, sugarcane, and corn. In the uncertain post-war economy, shade tobacco emerged as Quincy’s staple crop and the town soon became known as the “shade-grown leaf-tobacco capital.”

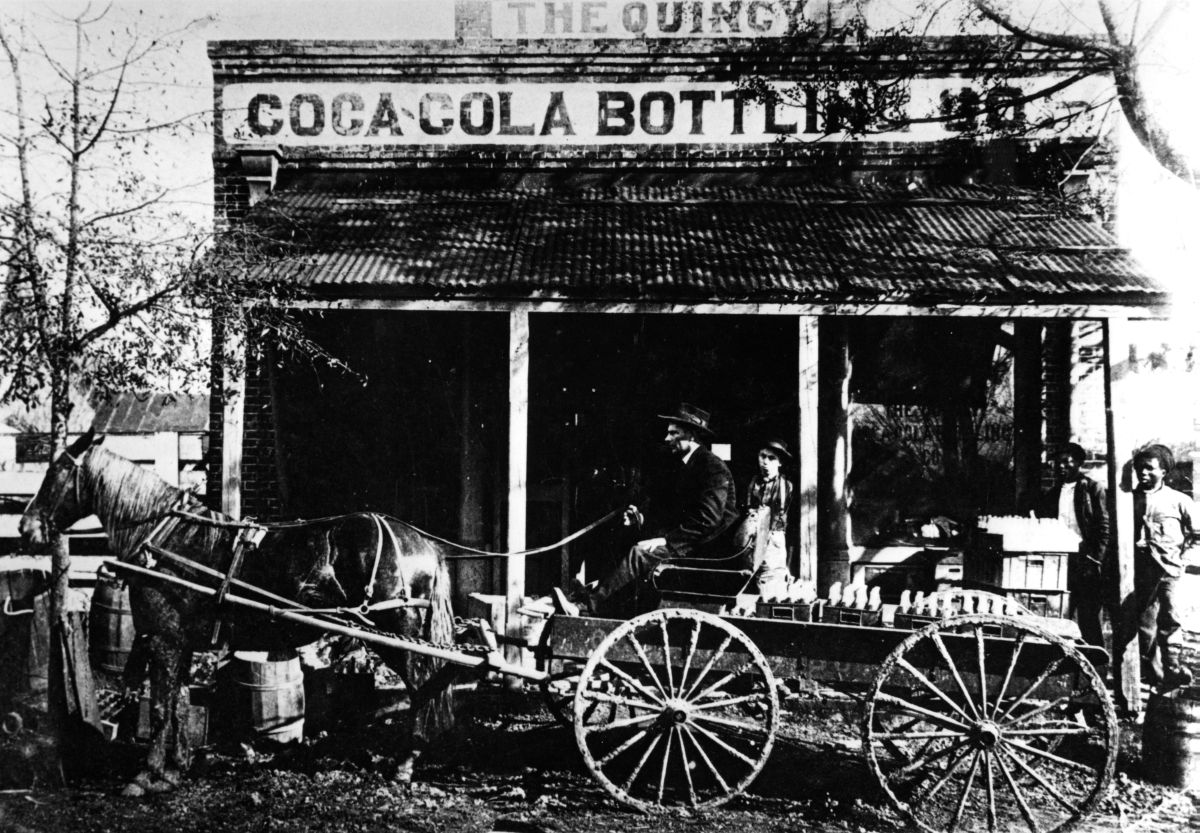

Though the shade tobacco crop certainly had potential to yield high returns, natural factors, like fluctuating soil fertility and capricious weather patterns, posed an investment risk. Enter the sweet stability of Coca-Cola, the best-selling saccharine treat whose production calls for little more than sugar and carbonated water. When Atlanta pharmacist John Pemberton first introduced Coke in the 1880s, the brand suffered from lackluster advertising and public skepticism–many consumers thought the product held addictive properties. But fresh marketing techniques turned the company around, and by 1909 Coca-Cola owned an estimated 379 bottling plants in the United States, including one in Quincy.

Atlanta-based company stakeholder W.C. Bradley sought to expand Coke’s operation, convincing his out-of-state colleague and President of the Quincy State Bank Pat Munroe to invest. In the 1920s, Munroe bought numerous shares of Coke stock for about $40 each and soon watched the values balloon. He strongly encouraged his friends and customers at the bank to do the same. Munroe’s son-in-law and former State Representative Bob Woodward, Jr. often retold the story of how his father went into the bank for a $2,000 farm loan. Munroe insisted on writing Woodward a $4,000 loan, if he promised to invest half in Coke stock. It paid. “Coca-Cola helped my family survive the depression…. It was like gold to the Quincy State Bank.” Quincy folklore recalls Munroe as a kind of coke evangelist. “Anyone who went in the door of the Quincy State Bank to borrow a quarter had his arm twisted to buy a nickel’s worth of Coca-Cola stock,” rumored one old-time resident. Those who ignored Munroe’s financial advice sorely regretted it later. After one patron refused the bank president’s suggestion to purchase $5,000 worth of the soda stock in the 1920s, his son lamented to a Florida Times Union reporter fifty years later that the shares would have hovered around $500,000 in value by 1975. By one estimate, a single share of Coca-Cola stock purchased in 1920 would be worth $6.4 million today, all dividends reinvested. Pat Munroe died in 1940, but the impact of his original decision to invest in the soft drink company lived on for decades in Quincy.

View of the Quincy State Bank building, nicknamed “the Coke bank” by locals, on the corner of Washington and Tennessee Avenue in Quincy, ca. 1920. Munroe served as president of the bank from 1892 until his death in 1940.

The philanthropy of some of the Coke millionaires helped to soften the harsh economic impact of the Great Depression and later episodes of economic downturn. In the 1970s, Quincy’s tobacco market dried up after Central and South American countries commandeered the market. As a result, the area suffered from high unemployment and low incomes. Although the Coke millionaires could not single-handedly reboot Quincy’s economy or eliminate systemic poverty, some of them have helped spruce up the city’s appearance over the years. Munroe’s daughter, Julia Woodward, along with other Coke millionaire heirs, Florence Brooks and Marcus and Betty Shelfer, donated a substantial portion of the $150,000 used to restore the Leaf Theater on Washington Street in 1983. Their largess also assisted in the renovations of the Centenary Methodist Church, the addition of the Robert F. Munroe school library, and the partial funding of the Girl Scout Camp on Lake Talquin. Though these cosmetic changes have certainly beautified Quincy, the town lost its claim as the richest small town in America long ago, after all of the original Coke investors passed on and many of their relatives moved away. According to the U.S. Census Bureau’s most recent calculations, Gadsden County’s level of per-capita income now ranks 59th out of Florida’s 67 counties. Moreover, Quincy’s poverty rate hovered around 27 percent in 2015, significantly higher than the state average of 15 percent. Despite these sobering economic trends, it is as safe a bet as any that Coca-Cola is still Quincy’s drink of choice.

Cite This Article

Chicago Manual of Style

(17th Edition)Florida Memory. "Quincy Goes Better with a Coke." Floridiana, 2017. https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/324844.

MLA

(9th Edition)Florida Memory. "Quincy Goes Better with a Coke." Floridiana, 2017, https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/324844. Accessed November 28, 2024.

APA

(7th Edition)Florida Memory. (2017, January 1). Quincy Goes Better with a Coke. Floridiana. Retrieved from https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/324844

Listen: The Assorted Selections Program

Listen: The Assorted Selections Program