Description of previous item

Description of next item

The Underground History of Florida Caverns State Park

Published November 11, 2016 by Florida Memory

For the past 74 years, the interpretive cave tours available at the Florida Caverns State Park have made the site one of the Sunshine State’s most unique attractions. Situated about one hour west of Tallahassee in Marianna near the Chipola River, the shimmering limestone caverns of northwest Florida regularly dazzle visitors. Aside from their obvious physical allure, the history of the Florida Caverns further illuminates the evolving social, economic, and environmental landscape of the state. The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) first developed the caves into a public tourist destination in the late 1930s, but humans have interacted with some of the caverns for much longer. Since officially opening to the public in 1942, the Florida Park Service has dutifully maintained the caverns. As a result of these conservation efforts, generations of spelunkers, hikers, and sightseers have relished the opportunity to explore the curiosities of Florida’s underground world.

Colored lights give added dimension to the cave formations in the “Cathedral Room” at Florida Caverns State Park, 2016.

The splendid mineral silhouettes inside the Florida Caverns did not form over a matter of years, decades, or even centuries. Rather, they are the result of 38 million years of falling sea-levels, which left previously submerged shells, coral, and sediment in the open air to harden into limestone. For the next several hundred thousand years, droplets of acidic rainwater passed through the ceiling of the porous limestone cave, and over time minerals bunched into icicle-like formations called stalactites. As the stalactites hung from the cavern’s top, water slowly trickled down to create mineral spires, known as stalagmites, on the cavern floor. In many rooms and hallways, the stalactites and stalagmites have joined to form full columns. Glistening draperies, soda straws, and ribbons complement the proliferation of stalactites and stalagmites, creating a distinct living environment for the cave-dwelling flora and fauna.

View of stalactites and stalagmites inside the Florida Caverns. The lowest point in the caverns is 65 feet below sea level, while the highest point is 125 feet above sea level. The temperature in the caverns hovers around 65 degrees Fahrenheit at all times, regardless of seasonal fluctuations. Blind salamanders, crayfish, and gray bats live among the underground limestone formations.

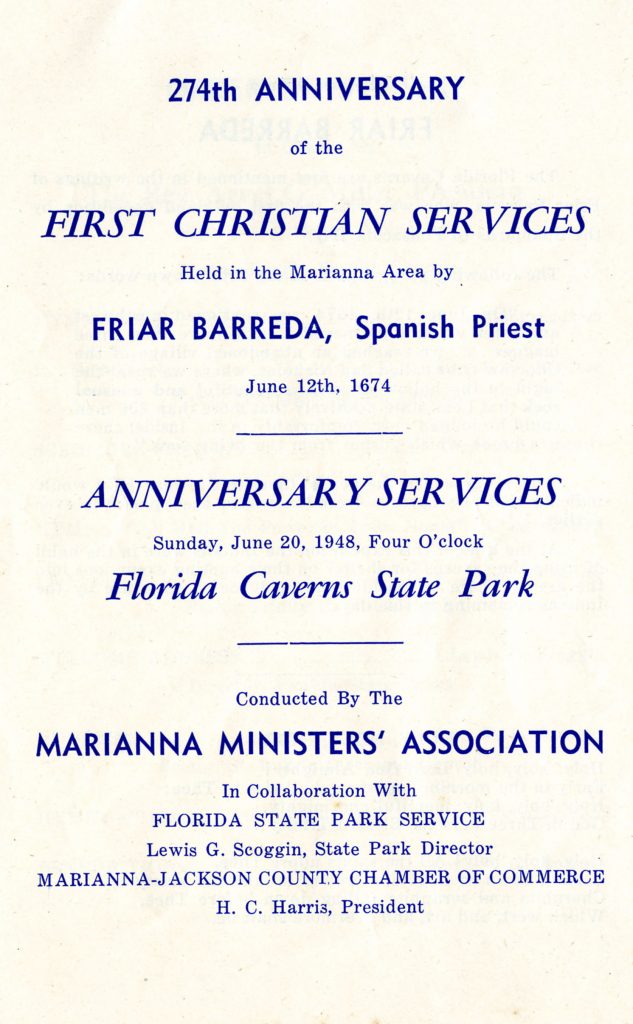

Archaeological discoveries of pottery sherds and mammoth footprints in several of the caverns predate European settlement in North America. But the site factors into Florida’s more recent history, too. In 1674, for example, Spanish missionary Friar Barreda allegedly delivered a Christian sermon amid the backdrop of the underground wonderland. Prevailing folklore also suggests a group of Seminoles trying to escape Andrew Jackson’s Indian removal expeditions of the early 19th century took refuge in the caverns. Further, the secluded underground openings have reportedly sheltered outlaws, runaways, and mischievous teenagers for centuries.

Program from services commemorating the 274th anniversary of the first Christian services held at the Florida Caverns in Marianna, 1947. Florida Park Service public relations and historical files (S. 1951), Box 1, State Archives of Florida.

The Florida Caverns remained one of the state’s best kept secrets until the 1930s, when the economic downturn of the Great Depression precipitated the expansion and creation of state and national parks. After President Franklin D. Roosevelt took office in 1933, his administration proposed a “new deal” for United States economy, enacting a series of sweeping measures intended to relieve the financial strain of some 12 million jobless Americans, or nearly a quarter of the workforce. One of those programs was the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). Nicknamed “Roosevelt’s Tree Army,” the CCC, which fell under the operation of the Florida Board of Forestry, was designed to conduct conservation work, including state park construction, while simultaneously providing employment, education, and training to enrollees. State forest officials spied commercial potential in expanding the state park system, and would ultimately utilize federally funded CCC labor to realize that vision. “They [tourists] soon tire of the races, nightclubs, and man-made recreation. They sit in the lobbies of our hotels wondering what to do with themselves. If a park system were shown on the highway maps and their wonders described in the literature of a state department, the tourists would flock to parks by the thousands,” wrote forester Harry Lee Baker to the Florida State Planning Board in 1934. One year later, the Florida Legislature created the Florida Park Service (FPS), an agency overseen by the Florida Board of Forestry. The FPS would operate in tandem with both the National Park Service and the Internal Improvement Fund. By the close of 1935, seven of Florida’s original state parks came under the control of the FPS, including the Florida Caverns.

CCC workers construct mess hall at the Oleno forestry training camp in Columbia County, Florida, 1935. With the establishment of the Florida Park Service, the CCC put thousands of unemployed Floridians to work developing state parks for public use.

In order to make the newly discovered series of caves accessible to tourists, CCC enrollees were paid approximately one dollar per day to work on the project from 1938 to 1942. Underground, the “gopher gang” removed hundreds of tons of soil and rock to create usable pathways and clearings large enough for people to walk through, while also installing a light and trail system to guide visitors through the caves. Above ground, CCC workers helped construct a visitor center, fish hatchery, and nine-hole golf course. With the onset of America’s involvement in World War II, the federal government discontinued the CCC, and work on the caverns project abruptly stopped. In 1942, the 1,300 acre Florida Caverns State Park officially debuted to the public, charging 72 cents for general admission.

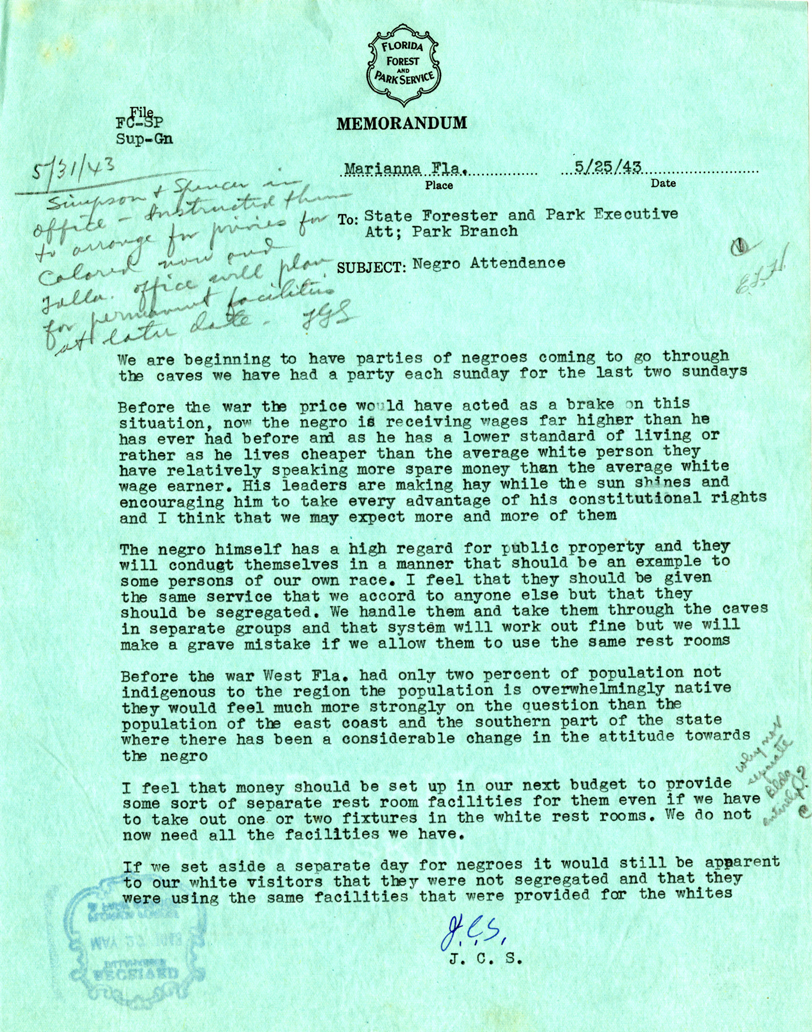

Thousands of visitors descended into the bowels of the “underground wonderland” during its first years of operation. The caves soon emerged as a popular Sunshine State tourist destination during and after WWII. As Florida’s total population more than doubled between 1940 to 1960, the FPS proposed several improvements and expansions to the state park to accommodate more visitors. No expansion issue was more sensitive, however, than the subject of segregated park restrooms for blacks and whites. A reflection of the separate and unequal Jim Crow South, the FPS designed the state parks system in the 1930s with only whites in mind–admission fares necessarily excluded African-Americans. However, the booming wartime economy of the early 1940s opened more economic opportunity to black Floridians, and in turn, lined their pockets with more disposable income to spend on recreation. Florida Caverns Superintendent Clarence Simpson observed the changing demographic of visitors and agreed that “they [African-Americans] should be given the same service that we accord to anyone else,” but warned that it would be “a grave mistake [to] allow them to use the same rest room.” Segregated bathroom facilities were eventually built for black patrons, and segregation persisted at all of Florida’s state parks until the Civil Rights Act of 1964 effectively outlawed the practice.

Letter dated May 25, 1943 from Superintendent of Florida Caverns J. Clarence Simpson to FPS Director Lewis Scoggin regarding segregated bathroom facilities. Florida State Parks project files (S. 1270), Box 1, State Archives of Florida.

In addition to offering integrated bathrooms and impressive guided cave tours, by the mid-1960s, Florida Caverns State Park also boasted new campgrounds, a swimming hole, expanded hiking and biking trails, and a bath house.

A young visitor is pictured standing inside the “Cathedral Room” on the cover of a Florida Caverns State Park promotional brochure, ca. 1950. State Library of Florida vertical file collection.

While perhaps not as well-known as Virginia’s Lurary Caverns or Kentucky’s Mammoth Cave, the eerie calm of the luminescent mineral contours at Florida Caverns State Park consistently draws droves of new and returning visitors each year. The next time you find yourself driving on the historic Highway 90 corridor in northwestern Florida, follow the signs for the caverns at Marianna, and uncover some of Florida’s underground history.

Interested in planning a trip to Florida Caverns State Park? Visit the Florida State Parks website for more information.

Cite This Article

Chicago Manual of Style

(17th Edition)Florida Memory. "The Underground History of Florida Caverns State Park." Floridiana, 2016. https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/324852.

MLA

(9th Edition)Florida Memory. "The Underground History of Florida Caverns State Park." Floridiana, 2016, https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/324852. Accessed February 26, 2025.

APA

(7th Edition)Florida Memory. (2016, November 11). The Underground History of Florida Caverns State Park. Floridiana. Retrieved from https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/324852

Listen: The Bluegrass & Old-Time Program

Listen: The Bluegrass & Old-Time Program