Description of previous item

Description of next item

Making Miami Modern

Published July 7, 2018 by Florida Memory

The Giller Building, located at 975 West 41st Street in Miami Beach, was officially added to the National Register of Historic Places on March 29, 2018. Built in 1957, the structure is named for its architect and first occupant, Norman Myer Giller, who made the building into a focal point for the architectural style he helped to make popular, Miami Modern.

Giller Building, located at 975 W 41st Street in Miami Beach. Photo courtesy of Max Imberman (2017).

Norman Giller was born in 1918 in Jacksonville but spent much of his childhood in Miami Beach and Washington, DC. He worked for a Washington architect right out of high school before taking a position with the U.S. Navy in Key West. With World War II on the horizon, Giller was transferred to the Army Corps of Engineers’ offices in Jacksonville to help design buildings for military bases in Florida and Georgia. Up to this point, his training had come on the job rather than from school, but Army rules required him to seek an architecture degree. Giller complied and graduated from the University of Florida in 1945.

After the war, Giller opened up his own architectural firm in Miami Beach. Business was booming–the war had forced most construction projects to the back burner, but once peace was restored the demand for new buildings skyrocketed. Even as a young architect just starting out on his own, Giller quickly landed more than a hundred clients. “The phone would ring,” he later recalled. “I’ve got a piece of property and I want to build an apartment building, I want to build a house, or I want to build some stores.” In those busy early days, Giller remembered having seven associates working on a single table to draw up plans.

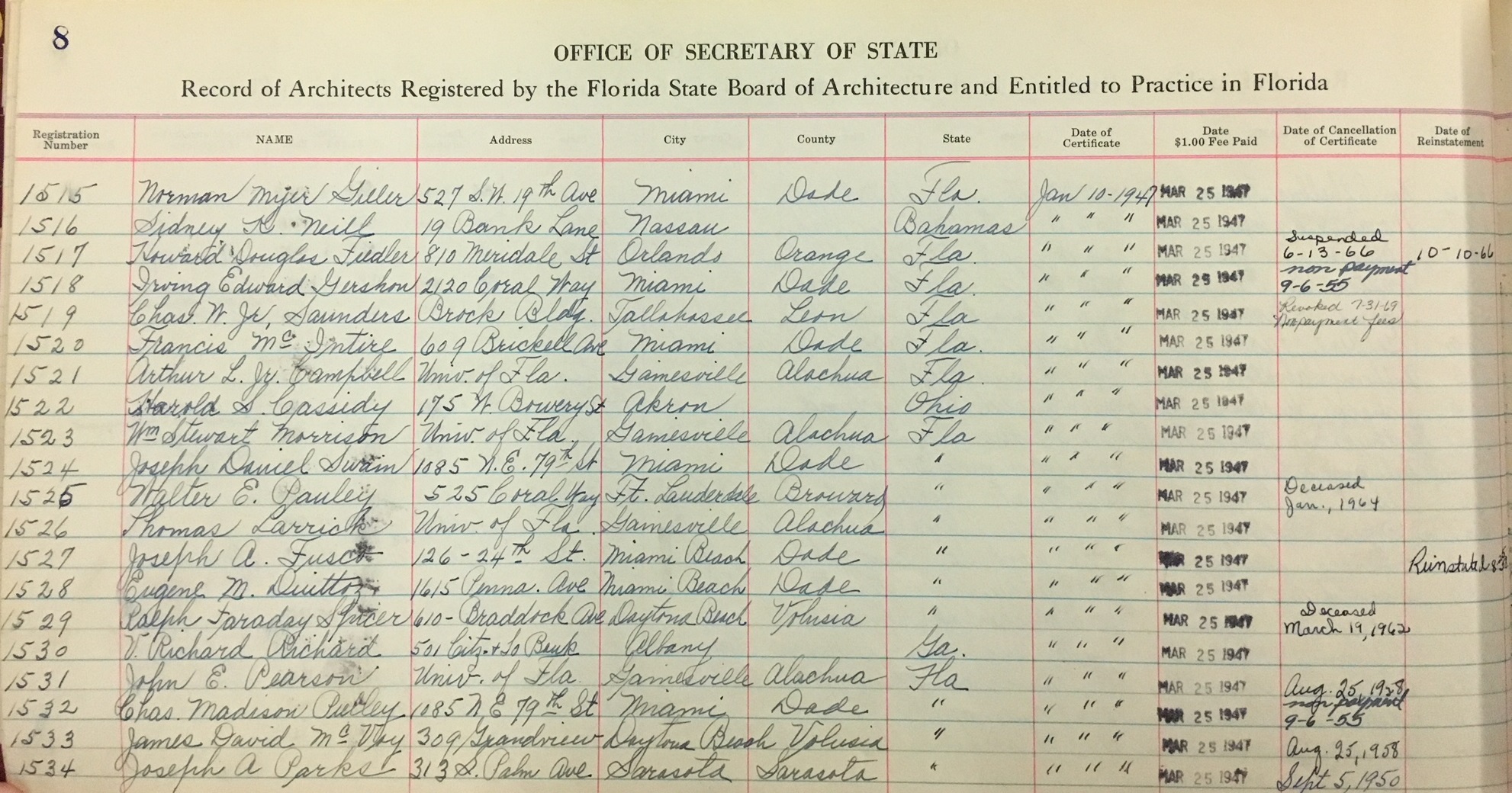

Record of Registered Architects maintained by the Secretary of State (Series S1195). Norman Giller held certificate #1515. State Archives of Florida.

From the beginning of his career, Giller was an innovator, even when it came to the technical details of design. Once during the war, the Army assigned him to build housing for a base in South Florida, and while the plans called for heating units, there was no plan for air-conditioning. Giller read up on a central heat and air-conditioning system that would do both jobs for one cost and convinced the military to use it. He was also one of the first architects to use PVC plumbing rather than traditional metal pipes, which tended to corrode and fail quicker when exposed to salt air and coastal soils.

Giller designed everything from nightclubs to banks to synagogues, but he is best remembered for his work on the hotels and motels that helped make Miami Beach a world-class tourist destination in the postwar era. He later noted that what architectural historians now call “Miami Modern” didn’t seem like anything special at the time. “Everybody was just designing what we called contemporary architecture of the time,” he said. “When you’re doing that, you’re not saying, ‘Gee, I want to design a [Miami Modern] building or an Art Deco building.'”

The Carillon Hotel in Miami Beach, designed by Norman M. Giller and built in 1955 (photo circa 1960).

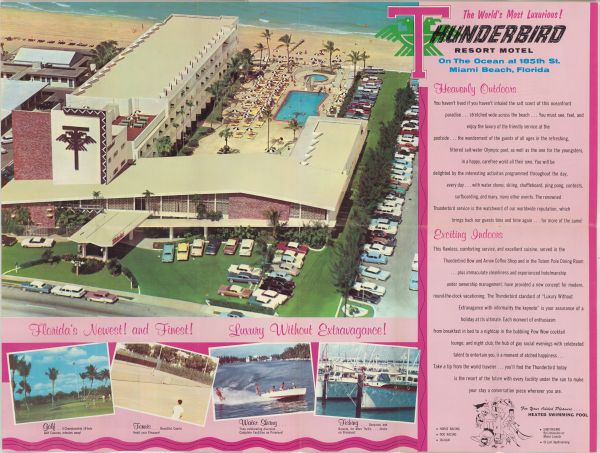

Miami Modern had its own look and feel, however. It reflected the optimism of post-World War II America, combined with an abiding faith in progress and reverence for Miami’s tropical qualities. Architects designing in this style used vivid colors, curved lines, glass walls, glass tile, colorful Formica surfaces and floating staircases to transport the visitor into the hopeful future many Americans felt was already coming their way. Giller brought this style to bear on large hotels such as The Carillon, as well as many smaller establishments of “motel row,” including the Thunderbird and Ocean Palm motels in Miami Beach. Most of these retained the traditional two-story floor plan–the four-story Thunderbird being a notable exception–but Giller took steps to incorporate some of the features that made his larger projects more exciting and comfortable. He eliminated interior hallways, instead having guests reach their rooms using covered walkways with the waves of the Atlantic Ocean crashing in the background. Brilliantly colored and whimsically shaped facades attracted the tourist’s attention from the highway, while the same shapes and colors repeated throughout the rooms and common areas.

View of the Thunderbird Resort Motel on Miami Beach, designed by Norman Giller. This promotional brochure includes images from throughout the building, illustrating Giller’s innovative architectural techniques. Click or tap the image to enlarge it (State Library Ephemera Collection).

The Giller Building is an adaptation of this style for an office environment. Giller built the original four-story structure in 1957 to house his growing architectural firm and a few additional tenants. The construction of the nearby Julia Tuttle Causeway in 1961 inspired Giller to expand the building with a six-story addition for more offices and tenants. The entire edifice is a celebration of the Miami Modern style that Giller helped promote, including floating staircases, glass tile mosaics on the exterior, and plenty of plate glass doors and windows.

Floating staircase inside the Giller Building. Photo courtesy of Max Imberman (2017).

Norman Myer Giller passed away in 2008, but monuments to his architectural contributions can still be found across Florida and throughout the Western Hemisphere. He designed motels in Key West, Jacksonville, Georgia, New Jersey, and even Canada, government buildings at Kennedy Space Center, and public facilities throughout Latin America. He was heavily involved in local civic affairs, chaired the South Florida chapter of the American Institute of Architects and received a number of awards and other honors for his work.

Is there a building in your Florida town that qualifies for listing on the National Register of Historic Places? Visit the Division of Historical Resources’ website to find out more about submitting a nomination!

Cite This Article

Chicago Manual of Style

(17th Edition)Florida Memory. "Making Miami Modern." Floridiana, 2018. https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/334332.

MLA

(9th Edition)Florida Memory. "Making Miami Modern." Floridiana, 2018, https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/334332. Accessed February 26, 2025.

APA

(7th Edition)Florida Memory. (2018, July 7). Making Miami Modern. Floridiana. Retrieved from https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/334332

Listen: The Bluegrass & Old-Time Program

Listen: The Bluegrass & Old-Time Program