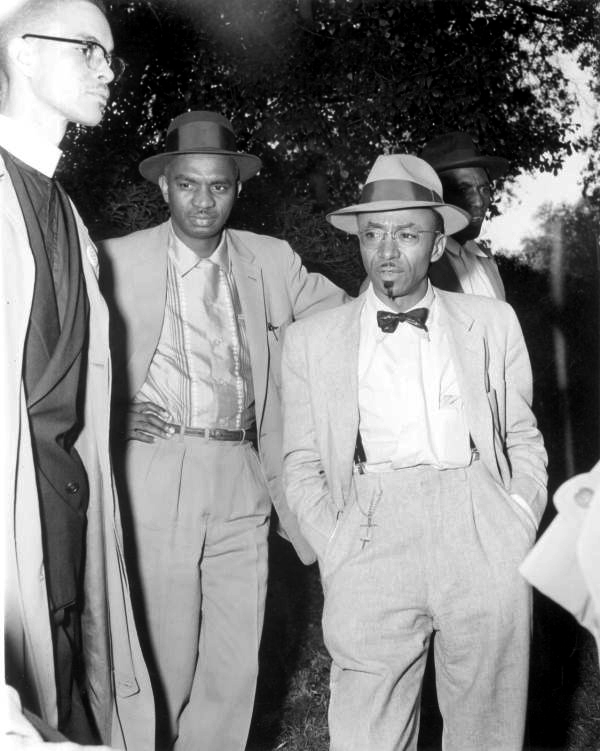

African-Americans in Tallahassee boycotted the bus system for nearly seven months after the arrest of two Florida A&M University (FAMU) students for sitting beside a white woman. During the boycott, African-Americans in Tallahassee used car pools to get to and from work and for other necessary transportation. Twenty-one members of the Inter-Civic Council were convicted on charges of operating an illegal transportation system for arranging the car pool without a franchise.

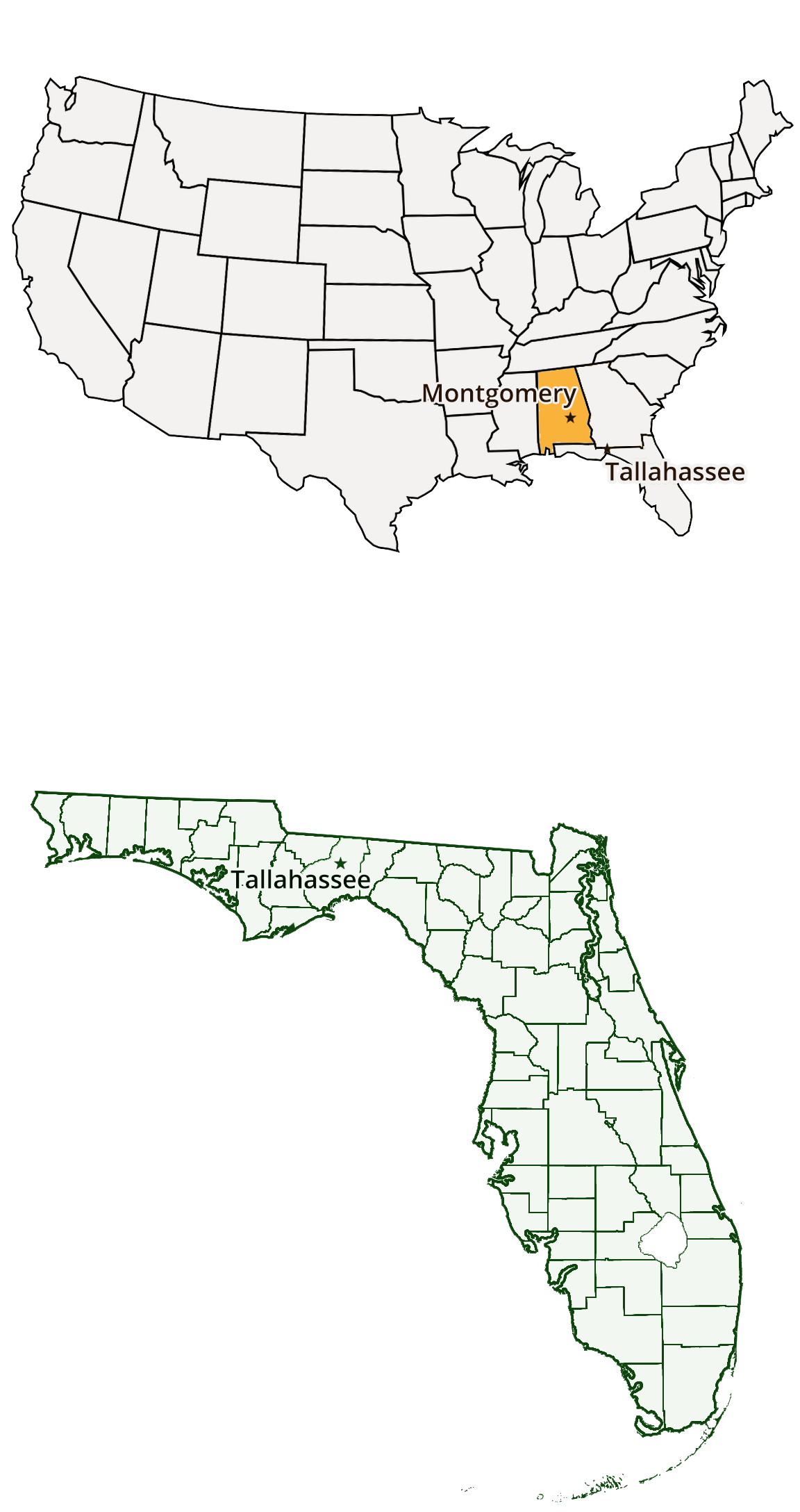

Reverend C.K. Steele, pastor at the Bethel Baptist Church, led the boycott of the city-run bus system. The protest began shortly after the Montgomery bus boycott and lasted primarily from May to December of 1956. According to Tallahassee historians Mary Louise Ellis and William Warren Rogers, “[c]ity commissioners and protesting blacks never achieved a formal settlement, but gradually the sight of blacks riding at the front of the bus became more common, and the battle moved to another front.”

On May 26, 1956, two FAMU students took action in Tallahassee, Florida. Wilhelmina Jakes and Carrie Patterson sat down in the "whites only" section of a city bus. When they refused to move to the "colored" section at the rear of the bus, the driver pulled into a service station and called the police. Tallahassee police arrested Jakes and Patterson. The students were charged with "placing themselves in a position to incite a riot."

Students at FAMU organized a campus-wide boycott of city buses. Soon, news of the boycott spread throughout the city.

Reverend C.K. Steele was the pastor at the Bethel Baptist Church. He formed the Inter-Civic Council to manage the logistics behind the boycott. Most of the protestors did not own cars. They had to find another way to get to work while they boycotted the buses. Supports offered to loan their cars and share rides. This was known as a carpool.

Twenty-one members of the Inter-Civic Council were arrested for organizing the carpools. They were convicted of operating an illegal transportation system without a franchise. The court fined the Inter-Civic Council $11,000.

Reverend Steele's slogan was, "I would rather walk in dignity than ride in humiliation."

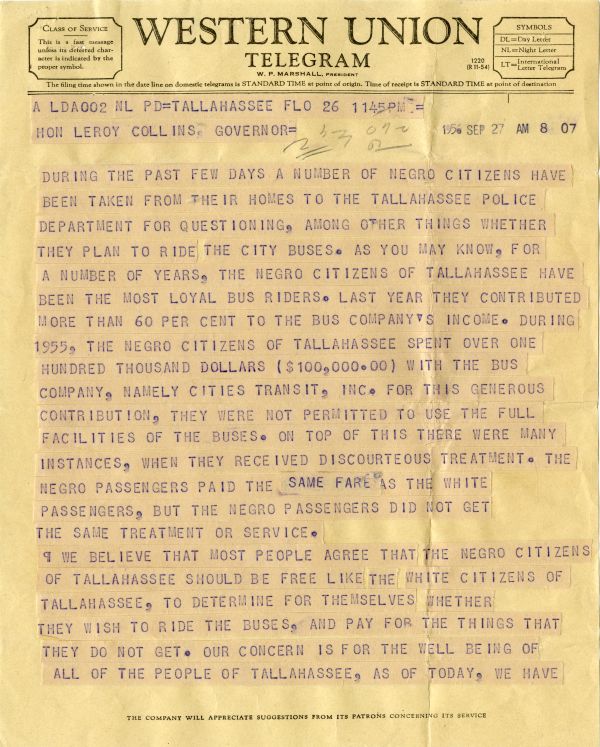

WESTERN UNION TELEGRAM

Hon Leroy Collins. Governor

During the past few days a number of Negro citizens have been taken from their homes to the Tallahassee police department for questioning, among other things whether they plan to ride the city buses. As you may know, for a number of years, the Negro citizens of Tallahassee have been the most loyal bus riders. Last year they contributed more than 60 per cent to the bus company's income. During 1955, the Negro citizens of Tallahassee spent over one hundred thousand dollars ($100,000.00) with the bus company, namely Cities Transit, Inc. for this generous contribution, they were not permitted to use the full facilities of the buses. On top of this there were many instances, when they received discourteous treatment. The Negro passengers paid the same fare as the white passengers, but the Negro passengers did not get the same treatment or service.

We believe that most people agree that the Negro citizens of Tallahassee should be free like the white citizens of Tallahassee, to determine for themselves whether they wish to ride the buses, and pay for the things that they do not get. Our concern is for the well being of all of the people of Tallahassee, as of today, we have

not heard of the police coming to the homes of Tallahassee's white citizens, and taking them to the police station, to have police officials question them as to their intentions to ride the buses.

Believing that you as a citizen of Tallahassee, and as a public official have an interest in the welfare of all of the people of Tallahassee both white and colored, we feel sure that you will not want to see the rights of Tallahassee's Negro citizen violated, because, they like a very large number of Tallahassee's white citizens are not riding the buses.

Very truly yours, for a better and a more prosperous Tallahassee for all of the people, both white and colored.

The Inter-Civic Council of Tallahassee

Cities Transit Company was forced to stop all buses for a month. They were losing too much money because of the boycott. Cities Transit tried to compromise. They offered to hire African-American drivers on the FAMU and Frenchtown routes. These routes ran through black neighborhoods in town.

Meanwhile, in response to the Montgomery bus boycott, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Alabama's segregated busing laws were unconstitutional. Soon, the court ordered Alabama to desegregate its public buses.

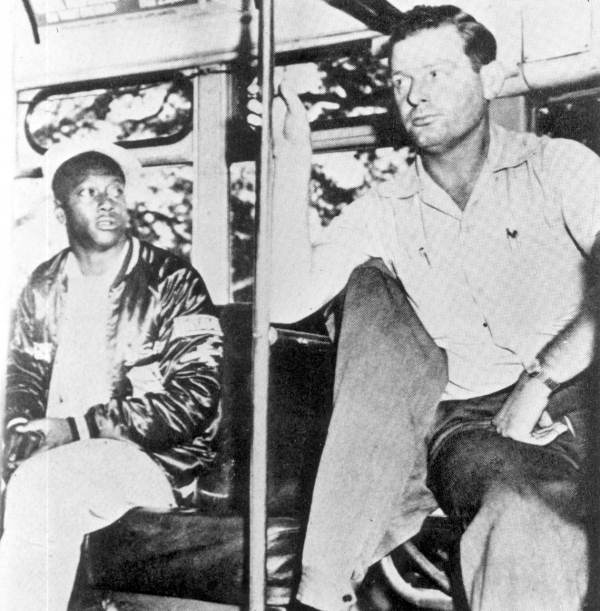

Inter-Civic Council leaders in Tallahassee decided to test whether the U.S. Supreme Court decision would be enforced in Florida. On December 24th, 1956, Tallahassee civil rights leaders sat in bus seats reserved for whites. Reverend C.K. Steele, Reverend A.C. Redd and Reverend H. McNeal Harris rode several buses sitting close to the front. Reverend J. Meta Rollins and Reverend Dan B. Speed also defied the seating convention on several buses that day.

Larger "front ride" demonstrations planned for December 27 were called off. Armed whites had threatened to confront the integrationists.

Under pressure from all sides, Governor LeRoy Collins suspended bus service in Tallahassee. On January 7, 1957 the city repealed the segregated seating ordinance. The city then enacted an "assigned seating" ordinance. The new ordinance tried to maintain segregated seating and comply with the Supreme Court decision.

By the summer of 1957, city buses in Tallahassee were integrated.

"City commissioners and protesting blacks never achieved a formal settlement, but gradually the sight of blacks riding at the front of the bus became more common, and the battle moved to another front," said historians Mary Louise Ellis and William Warren Rogers.

Through courageous nonviolent protest, the Tallahassee bus boycott succeeded. It set a precedent for the state. City by city, public transportation was desegregated in Florida.

Listen: The Assorted Selections Program

Listen: The Assorted Selections Program