Mary McLeod Bethune

Lesson Plans

Interview with Mary McLeod Bethune, ca. 1940

The awakening came to mother and father when able to sit down and read the newspapers and magazines and the Bible to them — that they had in their own home somebody who could do that — that was the greatest thrill.

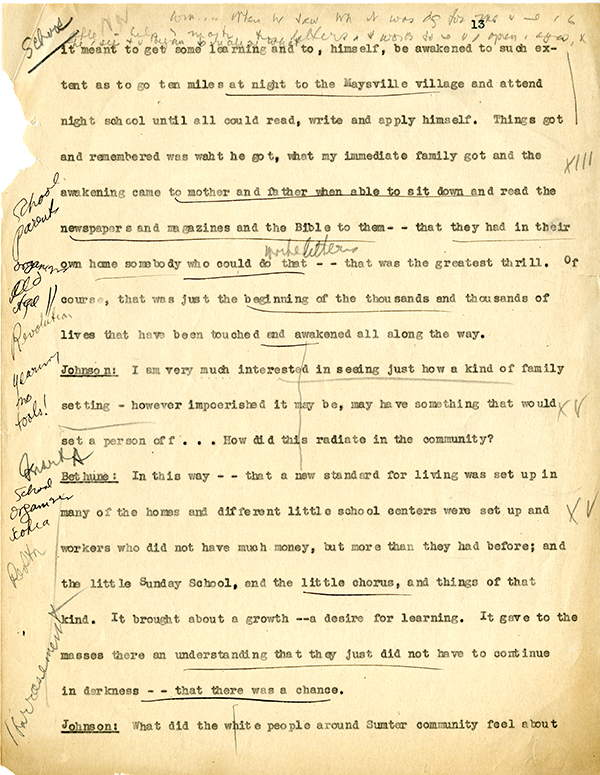

Page 13

When he saw what it was doing for me and that I was able to help him master his letters, and words do that he could open his eyes, and he could see and he began to realize what it meant to get some learning and to, himself, be awakened to such extent as to go ten miles at night to the Maysville village and attend night school until all could read, write and apply himself.

Things got and remembered was what he got, what my immediate family got and the awakening came to mother and father when able to sit down and read the newspapers and magazines and the Bible to them — that they had in their own home somebody who could do that — that was the greatest thrill.

Of course, that was just the beginning of the thousands and thousands of lives that have been touched and awakened all along the way.

Johnson: I am very much interested in seeing just how a kind of family setting – however impoverished it may be, may have something that would set a person off…How did this radiate in the community?

Bethune: In this way – that a new standard for living was set up in many of the homes and different little school centers were set up and workers who did not have much money, but more than they had before; and the little Sunday School, and the little chorus, and things of that kind. It brought about a growth – a desire for learning. It gave to the masses there an understanding that they just did not have to continue in darkness – that there was a chance.

Things got and remembered was what he got, what my immediate family got and the awakening came to mother and father when able to sit down and read the newspapers and magazines and the Bible to them — that they had in their own home somebody who could do that — that was the greatest thrill.

Of course, that was just the beginning of the thousands and thousands of lives that have been touched and awakened all along the way.

Johnson: I am very much interested in seeing just how a kind of family setting – however impoverished it may be, may have something that would set a person off…How did this radiate in the community?

Bethune: In this way – that a new standard for living was set up in many of the homes and different little school centers were set up and workers who did not have much money, but more than they had before; and the little Sunday School, and the little chorus, and things of that kind. It brought about a growth – a desire for learning. It gave to the masses there an understanding that they just did not have to continue in darkness – that there was a chance.

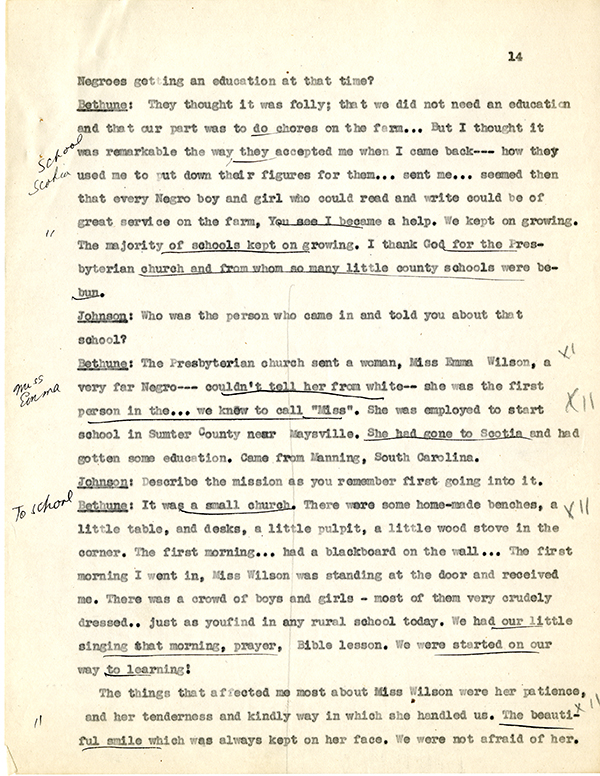

Page 14

Johnson: What did the white people around Sumter community feel about Negroes getting an education at that time?

Bethune: They thought it was folly; that we did not need an education and that our part was to do chores on the farm. But I thought it was remarkable the way they accepted me when I came back – how they used me to put down their figures for them… sent me… seemed then that every Negro boy and girl who could read and write could be of great service on the farm. You see I became a help.

We kept on growing. The majority of schools kept on growing. I thank God for the Presbyterian church and from whom so many little county school were begun.

Johnson: Who was the person who came and told you about that school?

Bethune: The Presbyterian church sent a woman, Miss Emma Wilson, a very fa[i]r Negro---couldn’t tell her from white—she was the first person in the…we knew to call “Miss”.

She was employed to start school in Sumter County near Maysville. She had gone to Scotia and had gotten some education. Came from Manning, South Carolina.

Johnson: Describe the mission as you remember first going into it.

Bethune: It was a small church. There were some home-made benches, a little table, and desks, a little pulpit, a little wood stove in the corner.

The first morning…had a blackboard on the wall…The first morning I went in, Miss Wilson was standing at the door and received me. There was a crowd of boys and girls – most of them very crudely dressed.. just as you find in any rural school today. We had our little singing that morning, prayer, Bible lesson. We were started on our way to learning.

The things that affected me most about Miss Wilson were her patience, and her tenderness and kindly way in which she handled us. The beautiful smile which was always kept on her face. We were not afraid of her. We could approach her at any time.

Bethune: They thought it was folly; that we did not need an education and that our part was to do chores on the farm. But I thought it was remarkable the way they accepted me when I came back – how they used me to put down their figures for them… sent me… seemed then that every Negro boy and girl who could read and write could be of great service on the farm. You see I became a help.

We kept on growing. The majority of schools kept on growing. I thank God for the Presbyterian church and from whom so many little county school were begun.

Johnson: Who was the person who came and told you about that school?

Bethune: The Presbyterian church sent a woman, Miss Emma Wilson, a very fa[i]r Negro---couldn’t tell her from white—she was the first person in the…we knew to call “Miss”.

She was employed to start school in Sumter County near Maysville. She had gone to Scotia and had gotten some education. Came from Manning, South Carolina.

Johnson: Describe the mission as you remember first going into it.

Bethune: It was a small church. There were some home-made benches, a little table, and desks, a little pulpit, a little wood stove in the corner.

The first morning…had a blackboard on the wall…The first morning I went in, Miss Wilson was standing at the door and received me. There was a crowd of boys and girls – most of them very crudely dressed.. just as you find in any rural school today. We had our little singing that morning, prayer, Bible lesson. We were started on our way to learning.

The things that affected me most about Miss Wilson were her patience, and her tenderness and kindly way in which she handled us. The beautiful smile which was always kept on her face. We were not afraid of her. We could approach her at any time.

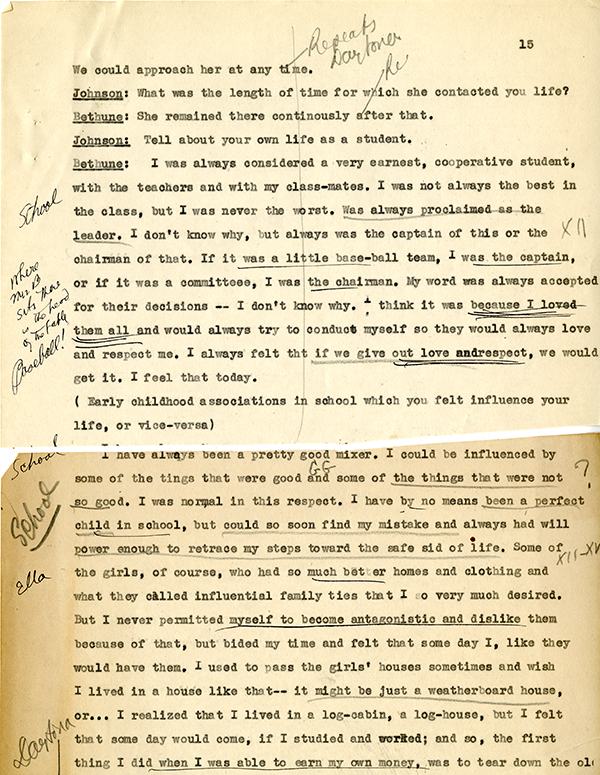

Page 15

Johnson: What was the length of time for which she contacted your life?

Bethune: She remained there continuously after that.

Johnson: Tell about your own life as a student.

Bethune: I was always considered a very earnest, cooperative student, with the teachers and with my class-mates. I was not always the best in the class, but I was never the worst. Was always proclaimed as the leader. I don’t know why, but always was the captain of this or the chairman of that. If it was a little base-ball team, I was the captain, or if it was a committee, I was the chairman.

My word was always accepted for their decisions – I don’t know why. I think it was because I loved them all and would always try to conduct myself so they would always love and respect me. I always felt that if we gave out love and respect, we would get it. I feel that today.

(Early childhood associations in school which you felt influence your life or vice-versa.)

I have always been a pretty good mixer. I could be influenced by some of the things that were good and some of the things that were not so good. I was normal in this respect. I have by no means been a perfect child in school, but could so soon find my mistake and always had will power enough to retrace my steps toward the safe side of life.

Some of the girls, of course who had so much better homes and clothing and what they called influential family ties that I so very much desired. But I never permitted myself to become antagonistic and dislike them because of that, but bided my time and felt that some day I, like they would have them.

I used to pass the girls’ houses sometimes and wish I lived in a house like that—it might be just a weatherboard house, or… I realized that I lived in a log-cabin, a log-house, but I felt that some day would come, if I studied and worked; and so, the first thing I did when I was able to earn my own money, was to tear down the old

Bethune: She remained there continuously after that.

Johnson: Tell about your own life as a student.

Bethune: I was always considered a very earnest, cooperative student, with the teachers and with my class-mates. I was not always the best in the class, but I was never the worst. Was always proclaimed as the leader. I don’t know why, but always was the captain of this or the chairman of that. If it was a little base-ball team, I was the captain, or if it was a committee, I was the chairman.

My word was always accepted for their decisions – I don’t know why. I think it was because I loved them all and would always try to conduct myself so they would always love and respect me. I always felt that if we gave out love and respect, we would get it. I feel that today.

(Early childhood associations in school which you felt influence your life or vice-versa.)

I have always been a pretty good mixer. I could be influenced by some of the things that were good and some of the things that were not so good. I was normal in this respect. I have by no means been a perfect child in school, but could so soon find my mistake and always had will power enough to retrace my steps toward the safe side of life.

Some of the girls, of course who had so much better homes and clothing and what they called influential family ties that I so very much desired. But I never permitted myself to become antagonistic and dislike them because of that, but bided my time and felt that some day I, like they would have them.

I used to pass the girls’ houses sometimes and wish I lived in a house like that—it might be just a weatherboard house, or… I realized that I lived in a log-cabin, a log-house, but I felt that some day would come, if I studied and worked; and so, the first thing I did when I was able to earn my own money, was to tear down the old

Page 16

Page 16 is missing.

Page 17

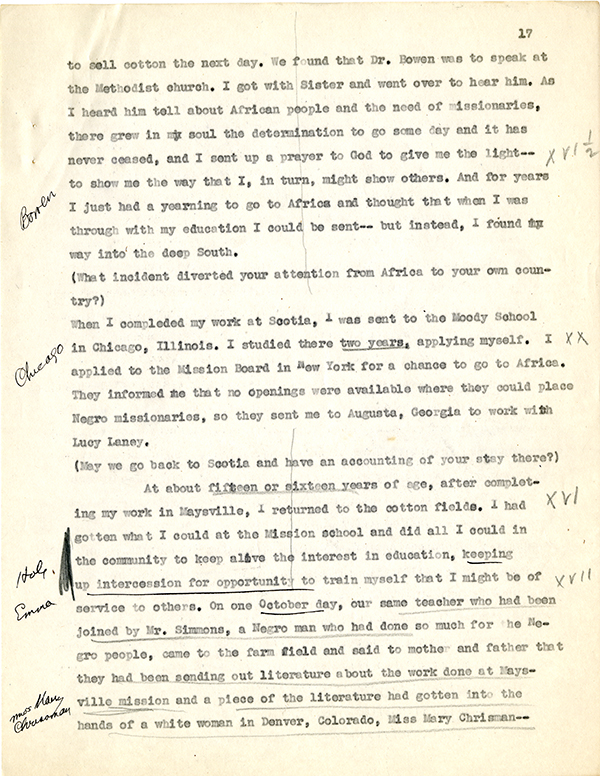

to sell cotton the next day. We found that Dr. Bowen was to speak at the Methodist church. I got with Sister and went over to hear him. As I heard him tell about African people and the need of missionaries, there grew in my soul the determination to go some day and it has never ceased, and I sent up a prayer to God to give me the light—to show me the way that I, in turn, might show others. And for years I just had a yearning to go to Africa and thought that when I was through with my education I could be sent—but instead, I found my way into the deep South.

(What incident diverted your attention from Africa to your own country?)

When I completed my work at Scotia, I was sent to the Moody School in Chicago, Illinois. I studied there two years, applying myself. I applied to the Mission Board in New York for a chance to go to Africa. They informed me that no openings were available where they could place Negro missionaries, so they sent me to Augusta, Georgia to work with Lucy Laney.

(May we go back to Scotia and have an account of your stay there?)

At about fifteen or sixteen years of age, after completing my work in Maysville, I returned to the cotton fields. I had gotten what I could at the Mission school and did all I could in the community to keep alive the interest in education, keeping up intercession for opportunity to train myself that I might be of service to others.

On one October day, our same teacher who had been joined by Mr. Simmons, a Negro man who had done so much for the Negro people, came to the farm field and said to mother and father that they had been sending out literature about the work done at Maysville mission. And a piece of the literature had gotten into the hands of a white woman in Denver, Colorado, Miss Mary Chrisman -- a rural school teacher who would often do dress-making after school hours – who became interested in what had been done for the Negro children in South Carolina. And (she) wrote to the teachers asking if they could find a little girl who would make good if given a chance, and that out of the money she was earning, she would give for that little girl’s education.

(What incident diverted your attention from Africa to your own country?)

When I completed my work at Scotia, I was sent to the Moody School in Chicago, Illinois. I studied there two years, applying myself. I applied to the Mission Board in New York for a chance to go to Africa. They informed me that no openings were available where they could place Negro missionaries, so they sent me to Augusta, Georgia to work with Lucy Laney.

(May we go back to Scotia and have an account of your stay there?)

At about fifteen or sixteen years of age, after completing my work in Maysville, I returned to the cotton fields. I had gotten what I could at the Mission school and did all I could in the community to keep alive the interest in education, keeping up intercession for opportunity to train myself that I might be of service to others.

On one October day, our same teacher who had been joined by Mr. Simmons, a Negro man who had done so much for the Negro people, came to the farm field and said to mother and father that they had been sending out literature about the work done at Maysville mission. And a piece of the literature had gotten into the hands of a white woman in Denver, Colorado, Miss Mary Chrisman -- a rural school teacher who would often do dress-making after school hours – who became interested in what had been done for the Negro children in South Carolina. And (she) wrote to the teachers asking if they could find a little girl who would make good if given a chance, and that out of the money she was earning, she would give for that little girl’s education.

Page 18

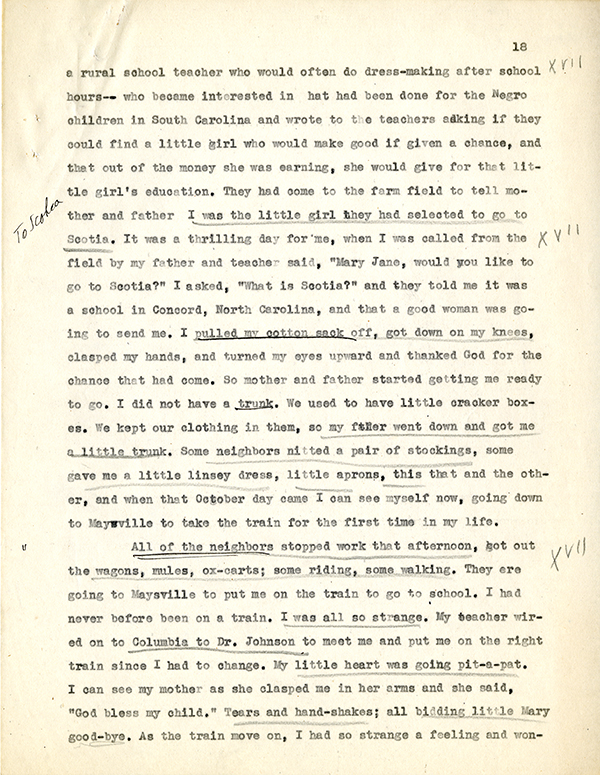

They had come to the farm field to tell mother and father I was the little girl they had selected to go to Scotia. It was a thrilling day for me, when I was called from the field by my father and teacher said, “Mary Jane, would you like to go to Scotia?”

I asked, “What is Scotia?” and they told me that it was a school in Concord, North Carolina, and that a good woman was going to send me.

I pulled my cotton sack off, got down on my knees, clasped my hands, and turned my eyes upward and thanked God for the chance that had come.

So mother and father started getting me ready to go. I did not have a trunk. We used to have little cracker boxes. We kept our clothing in them, so my father went down and got me a little trunk.

Some neighbors knitted me a little linsey dress, little aprons, this and that and the other, and when that October day came I can see myself now, going down to Maysville to take the train for the first time in my life. All of the neighbors stopped work that afternoon, got out the wagons, mules, ox-carts; some riding, some walking. They were going to Maysville to put me on the train to go to school.

I had never before been on a train. It was all so strange. My teacher wired on to Columbia to Dr. Johnson to meet me and put me on the right train since I had to change. My little heart was going pit-a-pat. I can see my mother as she clasped me in her arms and she said, “God bless my child.” Tears and hand-shakes; all bidding little Mary good-bye.

As the train moved on, I had so strange a feeling and wondered what it was all about. It seemed that as the train was puffing its steam it was saying, “Scotia, Scotia, Scotia.”

I asked, “What is Scotia?” and they told me that it was a school in Concord, North Carolina, and that a good woman was going to send me.

I pulled my cotton sack off, got down on my knees, clasped my hands, and turned my eyes upward and thanked God for the chance that had come.

So mother and father started getting me ready to go. I did not have a trunk. We used to have little cracker boxes. We kept our clothing in them, so my father went down and got me a little trunk.

Some neighbors knitted me a little linsey dress, little aprons, this and that and the other, and when that October day came I can see myself now, going down to Maysville to take the train for the first time in my life. All of the neighbors stopped work that afternoon, got out the wagons, mules, ox-carts; some riding, some walking. They were going to Maysville to put me on the train to go to school.

I had never before been on a train. It was all so strange. My teacher wired on to Columbia to Dr. Johnson to meet me and put me on the right train since I had to change. My little heart was going pit-a-pat. I can see my mother as she clasped me in her arms and she said, “God bless my child.” Tears and hand-shakes; all bidding little Mary good-bye.

As the train moved on, I had so strange a feeling and wondered what it was all about. It seemed that as the train was puffing its steam it was saying, “Scotia, Scotia, Scotia.”

Listen: The World Program

Listen: The World Program