Distant Storm: Florida's Role in the Civil War

A Sesquicentennial Exhibit

Florida’s Role in the Civil War

Before 1861: Florida’s Journey into Civil War

Slavery, Sectionalism, and Secession

The immediate impetus for Florida’s movement towards secession and civil war was the election of Abraham Lincoln to the presidency of the United States on November 6, 1860.

Like the rest of the seceding Southern states, the underlying tensions between Florida and the North had developed over decades. They centered on the fear that anti-slavery political forces would dominate the federal government, which would then prevent the expansion of slavery into recently acquired U.S. territories and push for the abolition of slavery in the South.

The opening of the South’s nightmare scenario came soon after Florida became a state in 1845. On August 8, 1846, Congressman David Wilmot of Pennsylvania attached an amendment to a House appropriations bill concerning the ongoing war with Mexico.

The Wilmot Proviso called for Congress to ban slavery in any territories that the United States might acquire from Mexico as a result of the war. Although it never became law, the Wilmot Proviso brought the question of slavery once again to the forefront of American politics and opened a breach between North and South that would grow wider and wider until 1861, when the South decided to sunder its attachment to the United States.

Although the Compromise of 1850 helped maintain the Union during the 1850s, that decade witnessed a succession of political confrontations between North and South over the issue of slavery. A minority of Northerners were abolitionists, but a majority stood firmly against the expansion of slavery into the western territories.

In the South, resentment of the growing dominance of Northern political and economic power led to increased popular support for the territorial expansion of slavery at any cost and the rejection of any political legitimacy for the Republican party, which most Southern politicians viewed as a vehicle for abolitionism and Northern economic control of the South.

These two fears reflected the Southern planter class’ preoccupation with the defense of the two institutions that allowed them to maintain political, economic and social control of the South: slavery and cotton.

Slavery in Florida Before 1821

African slavery in Florida began soon after the arrival of the Spanish in 1513. Due to the sparseness of Spanish settlement in the colony and the relatively liberal Spanish manumission laws, however, only a few hundred African slaves lived in Florida during the First Spanish Period (1565-1763).

Many of the Africans were free blacks, including runaway slaves living among Creek and Seminole Indians. The Africans, both slave and free, performed essential work for the Spanish and Native Americans: town and fort construction, agricultural labor, craft work and military service.

In order to bring in more settlers and to decrease the number of slaves working for their British enemies, the Spanish encouraged African slaves to flee the British colonies by offering them freedom in Florida in return for their conversion to Roman Catholicism.

The British had their revenge in 1763 when they gained control of Florida. It was this brief period of British rule (1763-1783) that began the large-scale importation of African slaves into the colony.

When the American Revolution began in 1775, there were some 3,000 slaves in British Florida, which was divided along the Apalachicola River into the administrative divisions of East Florida (capital at St. Augustine) and West Florida (capital at Pensacola).

The British used slaves to produce sugar, rice, indigo, naval stores and sea-island cotton. Loyalist refugees from South Carolina and Georgia sought security in Florida during the Revolution. The planters among these refugees brought their slaves with them.

By the end of the Revolutionary War in 1783, out of a total population in British East Florida of 17,375 persons, 11,285 were black. However, this population soon dwindled as the Spanish regained control. By 1786, the Spanish recorded 1,700 people living in St. Augustine: 127 of them were black.

Spain’s second period of control in Florida (1783-1821) saw the influx of a number of white settlers from the United States. The Spanish encouraged this migration to boost the population and productivity of its colony. Mostly Southerners and often slave owners, the settlers established plantations in East Florida, which the Spanish designated as all of the land in Florida east of the Suwannee River.

Spanish East Florida became a haven for slave smugglers, who transported slaves, many from Cuba or imported directly from Africa, into Georgia, where they brought a high price.

Although free blacks made up a considerable portion of the African population in Florida during the Second Spanish Period, pressure from the United States, where slaveholding states resented Spain’s policy of giving freedom to escaped slaves from the former English colonies, encouraged Spain to end its religious sanctuary policy in 1790. The Spanish also encouraged Americans and other foreigners to settle in Florida and contribute to the colony’s development in return for land grants.

Spanish appeasement did not satisfy the United States, however. Southern slave owners and many other white Americans could not accept the continued presence of armed blacks in Florida, where the Spanish supported a militia of free blacks and former slaves, and where bands of Black Seminoles (former slaves who lived with the Seminole Indians) presented an enticement for slaves in Georgia to escape into Florida.

Spain’s alliance with Britain during the Napoleonic Wars gave the United States a pretext to attack Florida during the War of 1812. For two years, an assortment of Georgia slave owners, militiamen and plunderers occupied Fernandina on Amelia Island and terrorized the Spanish and Anglo-owned plantations along the St. Johns River between the Georgia border and St. Augustine.

While most of the invaders withdrew by the end of the war in 1814, U.S. troops occupied Amelia Island outright in 1817, after arriving to oust a recent invasion of freebooters.

As American pressure on the Spanish mounted in East Florida, the United States also authorized incursions into West Florida, which had become a haven for runaway slaves and a homeland for Creek and Seminole bands.

On July 27, 1816, U.S. forces attacked the Negro Fort (a former British outpost) located about 60 miles south of the Georgia border on the Apalachicola River. As many as 270 blacks died as a result of a direct hit on the fort’s powder magazine. The attack set the stage for General Andrew Jackson’s invasion of Florida in 1817 and the struggle known as the First Seminole War.

As a result of this short conflict, Spain realized that it could no longer maintain control of Florida and in 1819 agreed to surrender the colony to the United States. Florida became a U.S. territory in 1821, when Spain relinquished official control.

The northern half of the territory became part of the Southern plantation economy. American settlers, some of whom had established plantations based on slave labor years before the U.S. takeover, continued to encounter black and Seminole resistance as the whites strove to expand their farms, plantations and slave system ever southward down the peninsula.

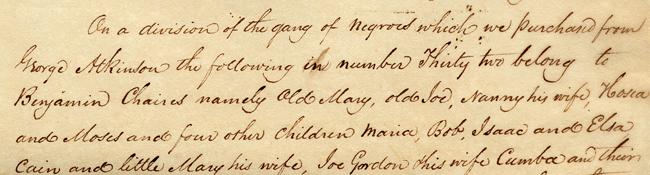

Benjamin Chaires and Thomas Fitch were two Southern planters who established plantations in East Florida during the last years of Spanish rule. The following document is an agreement between Chaires and Fitch for a division of slaves that they purchased from George Atkinson, a resident of Camden County, Georgia (Camden County is a coastal county bordering northeast Florida). In the agreement, Chaires, who became the wealthiest planter in territorial Florida, and Fitch name a total of 59 slaves to be divided between them.

Agreement for division of Negroes purchased by Thomas Fitch and Benjamin Chaires

(M93-1, Thomas Fitch Papers, 1818-1836)

Providence St. Johns 10 May 1820

On a division of the gang of negroes which we purchased from George Atkinson the following number Thirty two belong to Benjamin Chaires namely Old Mary, Old Joe, Nanny his wife, Hosea and Moses and four other children Maria, Bob, Isaac and Elsa, Cain and Little Mary his wife, Joe Gordon and his wife Cumbra and their infant child David, July and his wife Long Mary and their three children Simon, Judy and Peter, Ned a small fellow, Tom and his wife Louisa and their two children Betsy and David, Jim and his wife Amaritta and their child Pender, Beauty and his wife Big Nancy, Edward, Qua Billy and Joe one of the Gang we purchased of M. Kinne and Dupont and the following Twenty seven belong to Thomas Fitch namely Old Charlotte, Bob the Driver, Dye his wife, Billy and his wife Charlotte and Codando, Old Hannah, Mark, Murray, and Tenna, Anthony and his wife Lucy and their son Jemmy, Abraham, and his wife Nancy, Scipio and his wife Phillis and their three children January, Clarissa and Titus, Talbot and his wife Cornelia and their two children Dolly and Eva, Andrew, George and Big Jim, we agree that the same negroes shall remain at planting at St. Johns and the Beach place on Amelia Island till the present crop is gathered and in equal proportion to remain till the crop is prepared and sent to market.

Signed Duplicate sealed and delivered the day and year above written.

Ben: Chaires “Seal”

Thos, Fitch “Seal”

Listen: The World Program

Listen: The World Program

Enlarge this image

Enlarge this image