Lincoln Letters

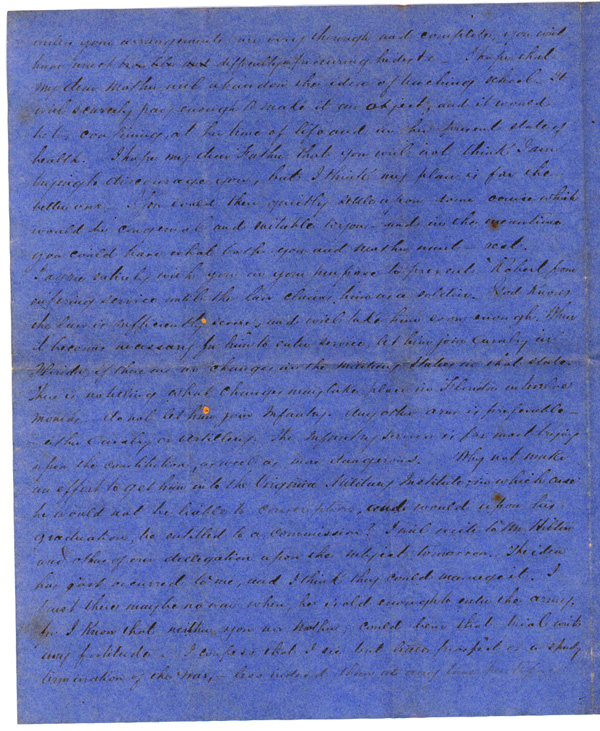

Letter, November 17, 1864, T. W. Brevard, "Camp Near Petersburg, Va" to "My Dear Father" (Page 2 of 4)

Date: November 17, 1864

Series: (M92-1) Box 6, Folder 1, Item 14

Lincoln Letters

Lincoln Letters

The re-election of Lincoln gives us the certainty of four more years of war, if the people of the North refuse to submit to the exhausting drain upon their individual population, made constantly necessary by the bloody and wasting campaigns of his main armies, and European Governments depart from the non-intervention policy. [1] The first contingency is extremely improbable. The Northern people are completely in subjection to the Washington Government. No ruler is more absolute than Lincoln, practically; he commands the entire resources of his county and wields the people of his nation as a sword. We have long ago ceased to hope for foreign intervention. There is no earthly chance for terms of agreement, which the re-constructionists urge (and I acknowledge that I am very glad of it) for Lincoln makes it a condition precedent even to the reception of the commissioners, that we shall lay down our arms and abolish slavery. It is fortunate for us that he makes the issue so broadly. It has already silenced many submissionists who admit themselves willing to comply with the terms preliminary to negotiations. We stand therefore at the expiration of nearly four years of bloodshed, in the face of a powerful military despotism, armed with every possible warlike appointment and equipment, determined not upon reestablishing the Union, but upon our subjugation, and we have no choice but to fight for it to the bitter end. Long ago I said, and I think so expressed myself in a letter to you, that the great danger to be apprehended in our struggle was the possible depression and arrest of fortitude on the part of our people—in and out of the army—in the event of Lincoln’s re-election, and the prospect of four years more of war. That test has come upon the country and may God grant the people of the South strength and grace to look the prospect bravely in the face, and to meet the issue honestly and defiantly.

Footnotes

[1] Since the beginning of the war in 1861, the South hoped and believed that a major European power—most likely Britain or France—would recognize the Confederate States and intervene in the war against the North. At first, this hope rested on the assumption that European textile mills could not long operate without southern cotton. European mills and workers did suffer, but Britain and other nations were able to turn to Egypt and India as alternative sources of cotton. Once the power of “King Cotton” failed to bring European recognition, the South hoped that Confederate arms would win European favor by defeating Union armies on Northern soil; however, Confederate defeats in the Antietam and Gettysburg campaigns ended this second option.

Listen: The Blues Program

Listen: The Blues Program