Photo Exhibits

Photo exhibits spotlight various topics in Florida history, and are accompanied by brief text intended to place selected materials in historical context.

Images of Florida Seminoles in the Sunshine State

Resistance and Removal

By the 1800s, Seminole culture was firmly established in Florida, but it was also threatened by the newly created United States, which desired the removal of Seminole peoples from the territory. A period of RESISTANCE and REMOVAL existed from the 1810s through the 1850s as the Seminoles resisted forced removal, fighting three wars in the process, while also moving progressively south.

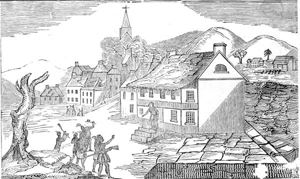

“An Indian town, residence of a chief,” (1835)

Image Number: RC07272

By the 1800s, after two centuries of European contact and disease, Seminoles and other southeastern people had abandoned the large earthen mounds and powerful chiefdoms of the Pre-Columbian eras.

Such Seminole towns as that pictured here, complete with wooden houses, ceremonial ball-fields, more localized leadership and a focus on small-scale farming, were commonly found throughout southern Georgia and northern and central Florida.

Many of Florida's current place-names, such as Tallahassee, Micanopy, Ocala, and Okeechobee, derive from these early Seminole towns. Historians today know that by this period, the Seminoles spoke Mikasuki and Muscogee and were closely related to the Creek cultures of Georgia and Alabama. (Image published by T.F. Gray and James of Charleston, S.C., in 1837.)

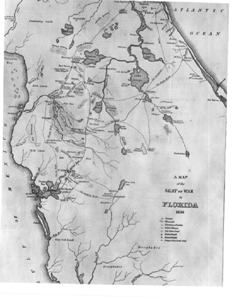

Map of the Second Seminole War (1836)

Image Number: RC09282

After the U.S. took control of Florida in 1821 (instigated in part by fighting between U.S. forces led by General Andrew Jackson and the Seminoles in North Florida between 1817and1818 -which today is referred to as the First Seminole War), it negotiated the Treaty of Moultrie Creek in 1823 to establish a Seminole reservation in Central Florida.

In 1832, the U.S. arranged a second agreement, the Treaty of Payne's Landing, which required the Seminole people to move west of the Mississippi within three years. Ratified in 1834, the treaty was signed by some but not all Seminole leaders. As the U.S. Army moved in to force the Seminoles' removal, many resisted, led by fighters such as Micanopy and Osceola. The result was a lengthy and bloody war between 1835 and 1842.

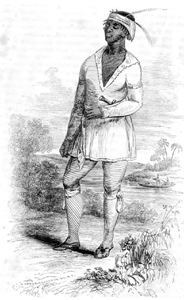

Micanopy, a Seminole chief (1836)

Image Number: RC0-470

Unlike the Americans, the Seminoles were not one nation with a single, unified leader. Instead Seminole society was comprised of various towns, clans, and small political organizations with a shared culture and language. This led to much of the confusion and accusations of betrayal by the Americans. Micanopy was one of the many Seminole leaders during the 1830s.

Monument at Dade Historic Battlefield State Park: Bushnell, Florida (1950s)

Image Number: PE0628

The first armed conflict between the resisting Seminoles and the U.S. government occurred on 28 December 1835 near present-day Bushnell, Florida. A group of 180 Seminole males attacked Major Francis Dade and his 103 soldiers marching from Fort Brook (Tampa) to Fort King (Ocala). Only three of the Americans survived. Ever since, the attack has been known as Dade's Massacre, and was the first battle of the Second Seminole War.

The site of the battle later became a National Historic Site and a Florida state park.

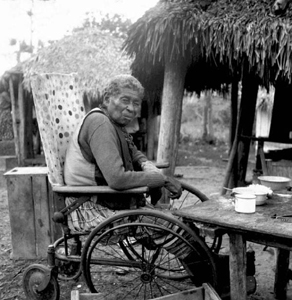

Black Seminole at Charlie Dixie Camp (1950s)

Image Number: PE0381

One of the reasons the American government was so adamant about removing Seminoles from a territory that was sparsely settled and seen as possessing little economic benefit was the presence of so-called Black Seminoles.

Freed and runaway African American slaves were often welcomed into Seminole society. Such a haven served as a magnet to enslaved African Americans throughout the Southeast, raising fears of slave owners that such a threat to their social structure must be eradicated.

Portrait of Gopher John (1842)

Image Number: RC08718

A Black Seminole and interpreter during the Second Seminole War.

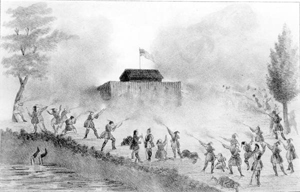

Rendering of a Seminole attack on a U.S. Army blockhouse (c. 1836)

Image Number: RC05221

Etching of Seminole men waiting to attack U.S. soldiers in New Smyrna Beach (1835)

Image Number: RC05471

It is unclear how much of this image is based upon eye witnesses and how much is creative license.

Drawing of the Indian Key Massacre (1840)

Image Number: RC02768

As was often the case in the 1800s, any conflict that resulted in American deaths were referenced as massacres, while those that resulted in Native American deaths were called victories.

In 1838, Dr. Henry Perrine, a botanist from Staten Island, New York, moved to Indian Key (75 miles north of Key West). With him were his wife Hester, son Henry Jr., and daughter Sarah.

In 1840, during the Second Seminole War, the key came under attack. The Perrine family hid in a turtle kraal under their house, while Dr. Perrine stayed above. He was murdered in what later became known as the Indian Key Massacre. The eleven-acre Indian Key became a state park, Indian Key Historic State Park, in the 1990s.

Ruins of the Dunlawton Sugar Mill: Port Orange (1900s)

Image Number: PC0753

Built in 1830, the sugar mill complex was a part of the Dunlawton Plantation and was destroyed in 1835 during the Second Seminole War. It was one of at least sixteen large plantations destroyed by Seminole fighters on Florida's East Coast. Incidentally, many of the plantation ruins from the 1830s were thought by many in the 1920s and 1930s to be the remains of Spanish colonial missions. The Dunlawton mill site was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1973, and later became a botanical gardens owned by Volusia County.

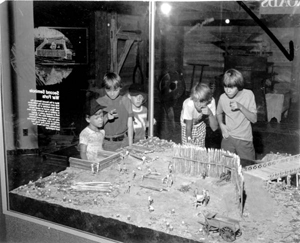

Diorama of the Second Seminole War at the Museum of Florida History: Tallahassee, Florida (1977)

Image Number: C684119

While the Second Seminole War ended in 1842, resulting in the removal of several thousand Seminoles to western territories, not all left Florida. Some of the remaining Seminoles fought for a third time with the U.S. between 1855 and 1858.

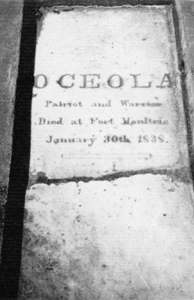

Tombstone for Seminole resistance leader Osceola: Fort Moultrie, SC (c. 1900s)

Image Number: PR04821

Osceola died while imprisoned at Fort Moultrie, South Carolina, where his body still resides.

Although neither a chief nor the only Seminole military leader, Osceola (whose name means "Black Drink Singer," after the popular Seminole tea made from Yaupon holly) emerged as the most well-known of the Seminole resistance fighters of the Second Seminole War.

By the 20th Century, he had become a folk hero, the subject of numerous books, the namesake of a Florida county, and the mascot for the Florida State University football team.

Listen: The Assorted Selections Program

Listen: The Assorted Selections Program