Florida in the Civil War

Photos and History

A Short History of Florida in the Civil War

Florida joined the United States in 1845. Fifteen years later, however, it was out again. After Abraham Lincoln was elected president of the United States on November 6, 1860, Florida and 10 other Southern states chose to secede, severing their ties with the rest of the country.

For years, differences between North and South over slavery and the federal government’s right to regulate it had divided the country. Political leaders in Florida and throughout the South considered Lincoln’s election the breaking point. If slavery were to survive, the South would have to leave the Union.

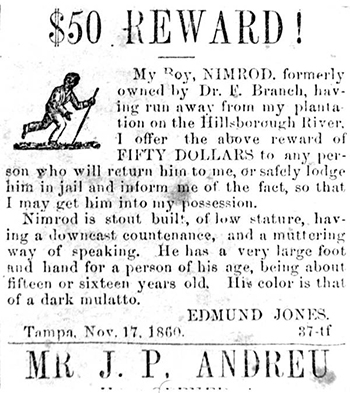

Tampa Newspaper ad offering a reward for the return of Dr. Edmund Jones' slave, Nimrod (1860)

Image number: N041082

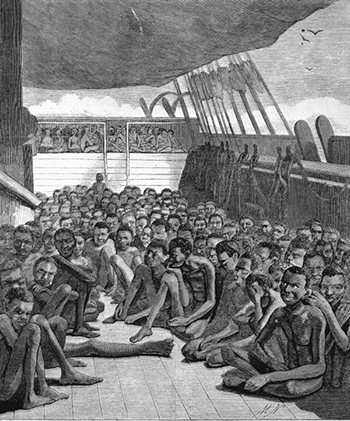

Slave deck of a ship brought into Key West (1860)

Image number: PR10116

Although Congress had outlawed U.S. participation in the international slave trade in 1807, it remained legal in other parts of the Western Hemisphere.

This ship and its human cargo were confiscated by the U.S. Navy as it was heading for Cuba in 1860.

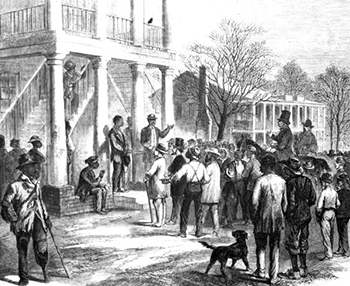

"Selling a freedman to pay his fine": Monticello, Florida (1867)

Image number: DG01993

Cotton, Slavery and Sectionalism

Middle Florida was the political and economic core of Florida. By 1830, most people in Florida lived in Middle and West Florida. Slaves made up the majority of the population, and their labor produced most of the food and cotton.

Cotton was the region’s most profitable crop. The growth of the cotton business encouraged immigration to Florida. Planters, merchants, craftsmen and small farmers moved to the territory in pursuit of their fortunes.

Planters believed federal limits on slavery threatened their livelihood. Even from Florida’s earliest days as a new state, it was clear how its leaders would handle this issue. William Dean Moseley, Florida’s first state governor, railed against the intrusion of federal power into the slavery question. The Florida General Assembly passed several resolutions supporting the expansion of slavery into new U.S. territories.

Plantation scene of laborers picking cotton in Florida (late 1800s)

Image number: RC03348A

This photograph was taken in the late 1880s, decades after the end of slavery. These workers were sharecroppers rather than slaves, but the methods they used for tending cotton fields were much the same.

Secession

Abraham Lincoln, the Republican Party candidate, won the presidential election of 1860. Lincoln gained most of the votes in the Northeastern and Midwestern states. The Republican platform opposed the extension of slavery in the territories, upheld tariffs (taxes on imports), and supported a federal railroad project.

Across the South, some Democrats called for Southern secession, while others supported the preservation of the Union. Each faction held separate conventions and nominated separate candidates. Stephen A. Douglas was the pro-Union candidate and John C. Breckinridge was the pro-secession faction’s choice.

The delegates to Florida’s secession convention, formally called the “Convention of the People of Florida,” assembled in Tallahassee to vote on whether Florida should secede. On January 10, 1861, 62 delegates voted for secession, while only seven voted against it.

A month after seceding, Florida joined six other Southern states to form the Confederate States of America. Former U.S. Senator and Secretary of War Jefferson Davis of Mississippi was inaugurated as president of the Confederate States on the steps of the Alabama Capitol.

Florida’s secession convention then adopted a new constitution which largely altered the existing Florida constitution by substituting “Confederate States” for “United States.”

The Cabinet of the Confederate States at Montgomery (1861)

Image number: RC05595

Union Forces

Florida had a small population, an incredibly long coastline, and a limited ability to produce weapons, tools and clothing. This made it an easy target for invading Union forces. Moreover, federal forces controlled Key West and Fort Zachary Taylor, as well as Fort Jefferson in the Dry Tortugas and Fort Pickens near Pensacola.

Portrait of John F. Bartholf: Pineland, Florida (187-)

Image Number: N028753

Bartholf was a Union military officer who commanded an all-black unit in South Florida during the Civil War. He later became a key leader in Manatee County's Republican Party. Bartholf is also referred to as the Father of Education in the Peace River Valley.

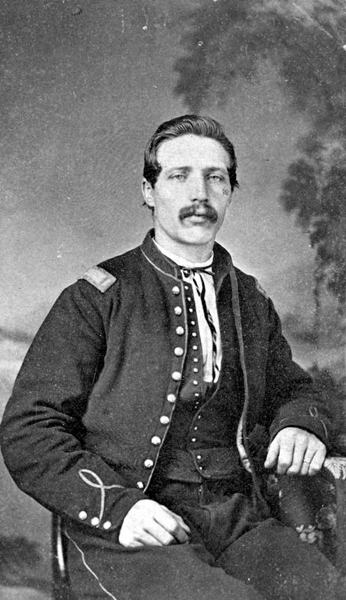

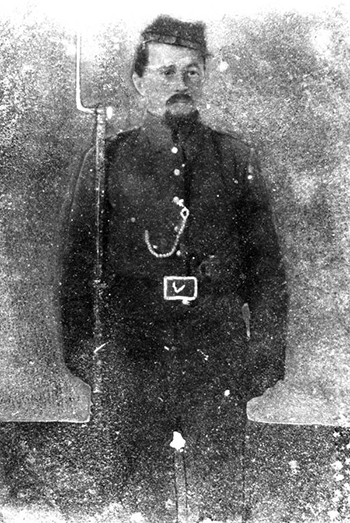

Frederick Jost (between 1861 and 1865)

Image number: N046331

Frederick Jost was a veteran of the 17th New York Cavalry who transferred to accept a commission in the 1st Florida Union Cavalry.

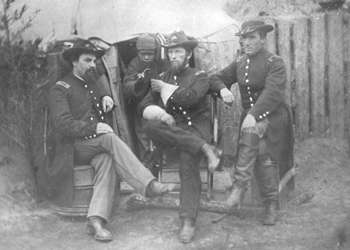

Officers of the 75th Ohio Infantry in Jacksonville (1864)

Image number: PR01717

A Call to Arms

Although Florida’s citizens had been divided over the question of secession before 1861, once the die was cast, they were generally loyal to the Confederacy. Many believed the war would be short. Some young men scrambled to enlist and train, hoping to get to the front lines before all the action was over.

However, there were pockets of anti-Confederate feeling across the state. As the war dragged on, allegiance to the Confederate cause began to fracture under the weight of deaths, hardships and disagreeable policies put into place by state and Confederate leaders.

Additionally, while some of Florida’s farmers depended on slavery, many did not. They might have agreed that the United States government’s interference with slavery was troubling, but over time they were less sure it was worth the high costs of the war.

Two policies in particular, conscription and impressment, were especially bitter to Floridians.

Rebel battery Pensacola, Florida (186-)

Image number: RC04842

Ninth Mississippi unit, Pensacola, Florida (1861)

Image number: RC02504

Conscripting Confederates

By 1862, the Confederacy faced a serious manpower shortage. On April 16 of that year, the Confederate Congress passed the Conscription Act. It was the first national draft in U.S. history. The act called for the enrollment of all white males between the ages of 18 and 35 in the military service of the Confederate States for a period of three years. Later it included men aged 17 to 50.

Owners of 20 or more slaves could be exempted. A man could also be excused if he hired a substitute to fight for him. These exceptions infuriated many Floridians. The common man was forced by law to serve in the military while wealthy men could buy their way out of fighting.

Some Floridians either avoided conscription entirely or deserted from the Confederate military. Men from Florida and other Confederate states hid in swamps and along the coast, sometimes with their families. Most deserters formed their own raiding bands or simply tried to remain free from Confederate authorities. Other deserters and Unionist Floridians joined regular Federal units for military service in Florida.

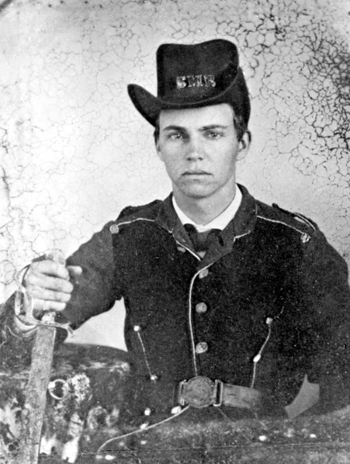

William D. Rogers (between 1864 and 1865)

Image number: RC11521

Enlisted May 1861, 1st Florida Infantry Regiment. Transferred in 1864 to 15th Cavalry ("SMR" on hat stands for "Simpson Mounted Rangers," which was company E of the 15th Confederate Cavalry). Captured with brother John Franklin Rogers at Pine Barren, Florida, by 1st Marine Cavalry and sent to Ship Island where he said they received kindly treatment. Died of dysentery on March 28, 1865. Buried on Ship Island, Mississippi, in grave #143.

Impressment

The Impressment Act of 1863 allowed agents of the Confederate government to seize food, tools, draft animals and other private property for military use. Payment, when it was given at all, was usually in Confederate treasury notes of dubious value.

Foodstuffs were the most common property seized in Florida. This made matters much more difficult for many Floridian families who already had very little to spare.

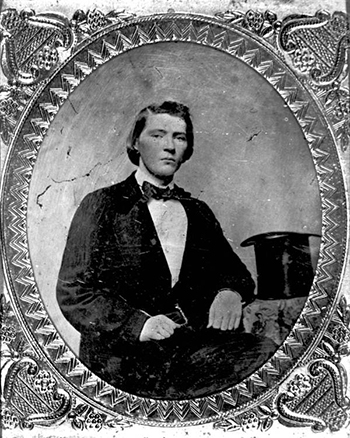

John A. Henderson (186-)

Image number: RC11550

Henderson moved to Tampa from Georgia in 1847 where he studied law in the office of James J. Gettis. He later moved to Tallahassee, where he became one of the state's leading corporate lawyers. He married twice, first to Mary Turman of Tampa who bore him a daughter named Flora Abijah; and second to Mattie Ward of Tallahassee with whom he had two children, John W. and Jennie.

He served in Company B of the 7th Florida Infantry Regiment as 2nd Lieutenant during the Civil War.

William Denham of Monticello (186-)

Image number: RC11524

Denham was a private in the 1st Florida Infantry. He was captured during his first skirmish, but he was released and recovered from his wounds. He later served in the 2nd Florida Cavalry and in Captain Scott's 5th Florida Battalion.

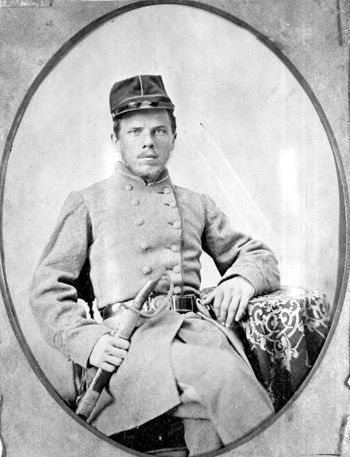

Confederate soldier Laurie M. Anderson (186-)

Image Number: RC11475

Laurie M. Anderson of Tallahassee was a member of the Bradford Light Infantry, Co. A, Florida Battalion. He died April 7, 1862, at the Battle of Shiloh.

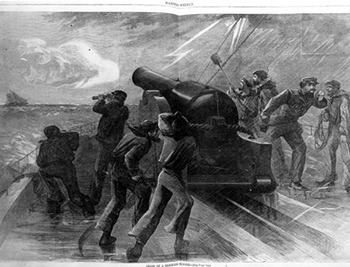

Blockade Running

Once the United States had wrapped its blockade around the state’s coastline, supplies became exceedingly difficult to obtain. Some daring individuals engaged in “blockade running,” or sailing small, fast craft past the Union blockade ships.

These blockade runners carried people, cotton, and other materials out of the state, and returned with much-needed supplies, such as ammunition, foodstuffs, coffee and weapons. Blockade running was dangerous business, and only a trickle of trade goods could be brought in and out of Florida.

As a result, prices were extremely high. Most Floridians found substitutes or learned how to get by without. Cornmeal replaced flour. Coffee was made from parched wheat, rye, sweet potatoes or corn. Citizens began reusing or repairing old tools and clothes rather than replacing them.

Chase of a blockade runner (1864)

Image number: RC05589

Slavery in Wartime Florida

Generally, Florida’s enslaved African-Americans remained at their posts on farms and plantations during the war. Fearful that their slaves might conspire to escape or rebel, owners were careful to conceal as much news as possible about the war. Slaves tended to feel the hardships of the war even more than their owners. Where an owner might be forced to substitute for a few luxuries in his clothing and food, his slaves might go without some necessities entirely.

President Lincoln issued his Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, declaring all slaves in the seceded states free from their bonds. Because Florida remained under Confederate control at this time, however, the proclamation would go unheeded until after the war.

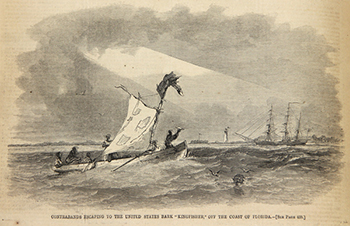

Union military activity in East and West Florida encouraged slaves in those areas to flee their owners in search of freedom. Of those slaves who reached the relative safety of Union-controlled territory, more than 1,000 enlisted in the United States military. Many Florida slaves working along the coast escaped to Union blockading vessels.

Escaped and freed slaves provided Union commanders with valuable intelligence about Confederate troop movements. They passed on news of Union advances to the men and women who remained enslaved. Planters’ fears of slave uprisings increased as the war went on.

Contrabands escaping to the United States bark Kingfisher off the coast of Florida (1862)

Image number: RC02674

Note: Escaped slaves who ended up under Union protection were referred to as “contrabands.”

Florida Beef

Florida was a vital source of beef and salt for the Confederacy. Florida beef became especially important after the Confederates lost control of the Mississippi River in 1864. The flow of beef from Texas was almost completely cut off. Florida’s vast supply of cattle became a critical food source for the Confederate Army.

Jacob Summerlin - Bartow, Florida

Image number: RC02467

One of Florida's most famous cattlemen, Jacob Summerlin was a prominent blockade runner during the war.

Confederate soldier Streaty Parker, of Bartow

Image number: PR01728

Joined 1st Florida Special Cavalry Battalion, Munnerlyn’s Guard Battalion which, protected Confederate cattle herds.

Salt

The Confederate army’s meat supply was preserved with salt. With the Union blockade in place, the Confederate states turned to local sources for this important mineral.

Large saltmaking operations appeared all along the Florida coast. Workers would boil seawater in large metal vessels. Once the liquid had evaporated away, the salt would be left behind. Workers would then package it and haul it away.

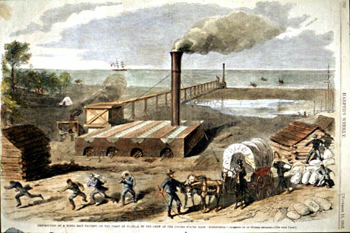

Destruction of a rebel salt factory on the Florida coast (1862)

Image number: RC03348

Destruction of a rebel salt factory on the coast of Florida by the crew of the United States bark Kingfisher, September 15, 1862.

Women on the Home Front

As more and more men volunteered or were conscripted for military service, women took over the administration of businesses and farms. They also supported the war effort by sewing clothing for soldiers, volunteering in hospitals, and collecting donations of money and goods badly needed by the troops. In a few cases, women even disguised themselves as men and fought as soldiers in battle.

Mrs. Columbus Augustus Boynton and son George William (ca. 1862)

Image number: PR08694

Mary Jane Safford

Image number: RC20846

Mary Jane Safford was a nurse with the Union army in the early days of the Civil War. She studied medicine and taught at the Boston University Medical School.

She moved to Tarpon Springs in 1882 and was one of the first women physicians in Florida.

The Battle of Olustee

In February 1864, Union forces landed in Jacksonville. They launched a major expedition into the interior of the state. The Union planned to cut off Confederate supply lines, locate recruits for black Union regiments, and establish a pro-Union government in East Florida.

Moving westward, the U.S. troops took Baldwin and Sanderson. Floridian troops retreated to find better ground for a counterattack.

In the largest battle fought in Florida, Union troops clashed with Confederates east of Lake City at Olustee. For several hours in the afternoon of February 20, 1864, fighting raged in the piney woods. Both commanders committed their forces only a few units at a time; however, the Confederates established a more effective position. As a result, the Federal units directly engaged in the battle faced a relatively larger number of Southern troops.

The Union’s General Seymour decided to withdraw his exhausted force. He deployed his reserve brigade, the famous 54th Massachusetts Regiment and the 35th U.S. Colored Infantry. The two black units delayed the Confederates long enough for Seymour to withdraw to Jacksonville. This was the only time the Union would push so far into the interior of Florida during the war.

Lithographic print of the Battle at Olustee

Image number: N046635

This lithographic print was published by Kurz and Allison. It is one of a series of Civil War battle prints.

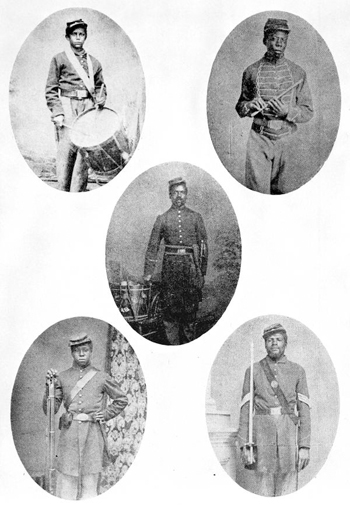

Five soldiers of the 54th Regiment of Massachusetts Volunteers (18--)

Image number: N039652

Top: Miles Moore, Musician, Company H; John Goosberry, Musician, Company E.

Middle: William J. Netson, Principal Musician, Company K.

Bottom: Private Robert J. Jones, Company I; Sergeant Henry Stewart, Company E.

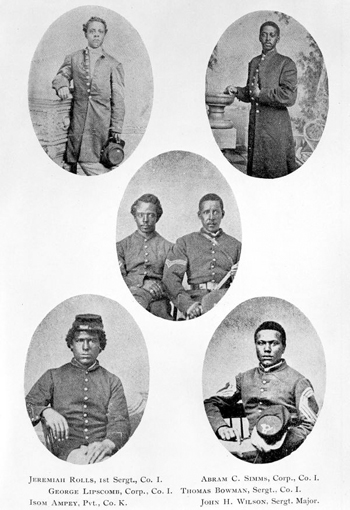

Soldiers of the 54th Regiment of Massachusetts Volunteers (18--)

Image number: N039653

Top: 1st Sergeant Jeremiah Rolls, Company I; Corporal Abram C. Simms, Company I.

Middle: Corporal George Lipscomb, Company I; Sergeant Thomas Bowman, Company I.

Bottom: Private Isom Ampey, Company K; Sergeant Major John H. Wilson.

Natural Bridge

The last significant battle of the war in Florida came in March 1865, when a Union force landed near St. Marks. The Union forces included several hundred Florida soldiers in the 2nd Florida Union Cavalry and most of the 2nd and 99th U.S. Colored Infantry regiments.

The Southern troops consisted of Florida cavalry and artillery soldiers, young and old militia members, and a small group of young cadets from the Florida Collegiate and Military Institute (later Florida State University) in Tallahassee.

The U.S. forces marched to Natural Bridge, where they hoped to cross the river and proceed to St. Marks. As the name suggests, this bridge was a natural span of solid rock across the St. Marks River.

The Confederates had the advantages of a solid defensive position, more cannons, and, by the end of the battle, more troops. The Union troops broke off the battle and retreated to the safety of the coast. The Confederate victory ensured that Tallahassee would remain in Southern hands for the remainder of the war.

Thaddeus Preston Tatum - Tallahassee, Florida

Image number: N042829

Thaddeus Preston Tatum was born in 1835 and died in 1873. He fought in the Battle of Natural Bridge, was a druggist by trade, and was mayor of Tallahassee in 1869 and 1870.

Lewis Thornton Powell, also known as Lewis Payne (186-)

Image number: RC11477

Undoubtedly the most notorious of all the Florida Civil War soldiers was Lewis Thornton Powell. Powell enlisted at age 17 in the “Hamilton blues,” Captain Henry Stewart’s company of the 2nd Florida Infantry.

Wounded and captured at Gettysburg, Powell escaped and joined John Mosby’s partisans. Powell later became involved in John Wilkes Booth’s plan to kill President Lincoln.

The End of the War

By the spring of 1865, the war was coming to a close. After the fighting ended in April, Union troops were dispatched throughout the former Confederate states to maintain order and administrate their transition back into the Union. Troops arrived in Tallahassee on May 10 to receive the surrender of Florida’s Confederate forces. On May 20, the United States flag was hoisted.

Listen: The World Program

Listen: The World Program