Pestilence, Potions, and Persistence Early Florida Medicine

Epidemic Disease and the Establishment of the Board of Health

Yellow Fever, Hookworm, and Clean Cities

Public Health Beyond Yellow Fever

Leprosy, cholera, typhoid fever, and other deadly diseases caused public alarm and required coordinated state effort. Endemic illnesses, such as hookworm, required political and scientific leadership.

Within three decades of establishment of the Board of Health, better regulation to ensure sanitary drinking water had begun to reduce instances of diseases such as hookworm, and more effective quarantining and more extensive state-run stations had allowed the state to limit the spread of yellow fever epidemics.

In 1908, an aggressive health education program increased awareness of hookworm, and the Board began paying physicians for each indigent case of hookworm they treated. The Florida example became a model for national efforts to combat hookworm.

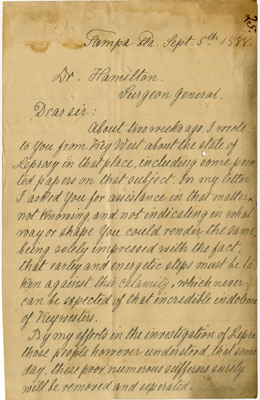

Warning of the Imminent Threat of a Leprosy Epidemic

In this letter, a Dr. Berger, in exile in Tampa after having fled Key West, has written to Dr. John B. Hamilton, the United States Surgeon General, warning of the imminent threat of a leprosy epidemic emerging from Key West, even while Florida was experiencing a yellow fever outbreak.

Referring to the “incredible indolence of Keywesters,” he cites Dr. Porter and the Key West Board of Health as the leaders of the opposition to his efforts to separate lepers from the city’s population and make the epidemic widely known outside the city.

Berger states that there were at least 50 current cases of leprosy in the city, with another 100 possible latent cases.

Dr. Wall, the health officer of Tampa, had confirmed with the author the diagnosis of leprosy in a 22-year-old man there who had come from Havana, Cuba, by way of Key West. Hamilton referred the letter back to Porter, as he was acting as the “surgeon in charge of government relief measures.”

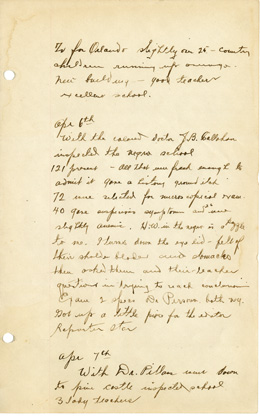

Hookworm Diary

C. T. Young, a leading doctor in the hookworm campaign, recorded encounters with parents and teachers.

While they often expressed support for hookworm eradication, parents sometimes opposed tests and medicine for religious reasons.

Young documents in the diary incidents of encountering other serious diseases such as scarlet fever while examining children suspected of being infected with hookworm.

He encountered teachers who gave firsthand accounts of the effects of hookworm and most often agreed with the pressing need for treating sick students. However, some teachers made “excuses” for not pushing parents for treatment, such as being too overworked to speak to them, or expressed a lack of faith that parents would allow intervention.

The Board and Dr. Young stressed the importance of proper home waste disposal and sanitation, as well as better sewage services for communities. The campaign brought Young and his colleagues face to face with Florida’s most impoverished citizens, and with hundreds of patients with little or no health care.

Young recorded meeting with school boards to explain the “pernicious bloodsucking” parasites that caused hookworm, and working with black physicians in order to bring testing and treatment to African-American children.

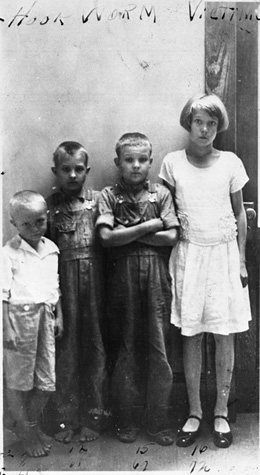

Hookworm and Poverty

Children of J.D. Tillman - victims of hookworm: Leon County, Florida (1931)

L-R: LeRoy Tillman (age 8, 41 lbs), George (age 12, 61 lbs), Joseph (age 15, 67 lbs), Mildred (age 16, 72 lbs).

Victims of hookworm were most often poor, and the effects of hookworm on poor children and adolescents were considered by reformers to be one of the contributing factors in the inability of poor citizens to achieve success and pursue education.

State officials viewed hookworm as clearly associated with poor sanitation and community and household hygiene, areas of increasing concern in the last decade of the 19th century in the South.

Disease and sanitation in dense urban areas and impoverished regions of the rural South were viewed by Progressive Era reformers as a cause of endemic poverty.

Listen: The World Program

Listen: The World Program